Lavanya had woken up to the early morning phone call with a start. “Laavu?” Pillai Uncle’s voice had sounded hollow. “It’s about your father”. “Yes?” she breathed into the phone, her heart pounding. “Heart Attack. We couldn’t wait,” Pillai Uncle continued. “We cremated him according to the Hindu rites this afternoon. By the lotus pond. He..he wanted it there”. “Yes,” Lavanya had managed to say, her stomach tightening.

It had taken her a whole week to get her papers and visa together. She barely noticed the cold, velvet undulations of the English country side as the train sped to Heathrow; her mind already on the tall humid palm grove, the dark green lotus pond and her old neighbours in Trivandrum’s St. Mary’s Lane. And now, here she was; hand on the iron gate of her father’s house, searching for Malayalam words to greet Pillai Uncle, her father’s close friend and neighbour, who was walking towards her, swinging his umbrella. “Laavu,” he said. “Long time..”.

Lavanya was back at home in Kerala after a long, long time. No. Only fifteen years, she corrected herself as she stepped into her father’s dream house: The Buckingham Palace. She had realized how inappropriate the name was when she stood shivering in front of the real Buckingham Palace, years later. The Indulgence was what she called this house now; another monument to the excesses of Gulf money in St. Mary’s Lane. Their old, lovely tile roofed Nalukettu house was demolished after her father’s stint as an accountant in Dubai and a three-storied monstrosity had risen in its place.

“There is a lot of work to be done,” said Pillai uncle, once they were inside. “Paper work related to the house, personal belongings…everything…I can help..,” he trailed off as Lavanya looked around the house that once was her home. She ran her fingers over the orange paisley upholstery in the living room that had faded over the decade of her absence. There was her father’s armchair, where he often sat brooding. After her mother’s death when she was only seven, her father had always been a background hum in her life; persistent and invasive, audible only to her.

Lavanya paused, a little dazed. “Kunjamma can stay here with you,” Pillai Uncle said, offering the services of his cook. “No. No. Thank You. I need some time…some time to think,” Lavanya said slowly, turning to Pillai Uncle. “Yes. Yes,” agreed Pillai Uncle gathering his big black umbrella.

A wave of tiredness washed over Lavanya after she had taken leave of Pillai Uncle. It was eerie to be in the house, again. Alone. She peeked into the kitchen. A faint aroma of spices clung to the walls. She looked into her father’s room; the antique four poster bed that took up most of the space. She could almost see her father sitting on his bed. And his eyes: sad, searching, apologetic.

Sensing her own unease, Lavanya quickly walked into the library: her favourite room in the house. She had always liked the tall windows that overlooked Pillai Uncle’s carefully manicured garden. The white lined bookshelves were crammed with books, magazines and other objects d’art. The antique bronze statue of the dancing Nataraja still stood in the same corner and the bejewelled painting of Lord Ganesha still gleamed quietly.

The carved rosewood swing had been in her mother’s family for generations. It had been a refuge for her in good times and bad. All those tears she had shed on the swing when her beloved mother died; all those lovely afternoons she spent reading Enid Blyton books with her friend Nandini Kutty. And Usha. She had forgotten to ask Pillai Uncle about her friends. She rested her head on the lumpy cushion on the swing and listened. The house was still. Somewhere outside, the gardener was husking coconuts. Thwack. Thwack. Maniya, she remembered. That was the gardener’s name. She began to swing to and fro. Somewhere she heard the shouts and pops from the badminton game. She remembered the badminton court at Paradise Apartments; the Wednesday afternoons. She drifted off into a jetlagged slumber.

She dreamed. Her fingers…her fingers were frozen. She was paralyzed. She was running…running…fast…faster…

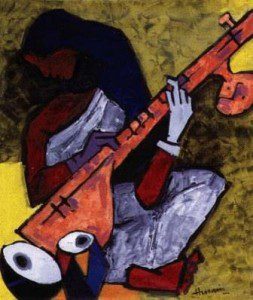

Lavanya woke up with a start, her heart racing. Breathless and parched, she drew herself to a sitting position on the swing. Lavanya took in the dark, sharp dancing shape of Lord Nataraja; the rows of books, everything. She was drawn to one particular object standing against the far wall, by the prayer altar: her mother’s Veena. No. Her Veena. She stumbled over to the large wooden body of the lute and plucked at one of the four playing strings. The room echoed momentarily with an ethereal, mellifluous twang.

Many years ago, dressed in a red Pavadai , Lavanya had run across the central courtyard of her Nalukettu house, with her pigtails flying. “Happy Eighth Birthday,” her father had said, leading her to the family prayer altar where her present lay wrapped in raw silk. Blushing prettily, Lavanya had knelt down and unfolded the fabric gently to reveal the body of her mother’s Veena. “Your mother used to play this; it is yours now,” said her father. “You will be starting music lessons with Saraswathy Aunty next week,” he said, leaving her with thoughts of a mother, she missed.

Saraswathy Aunty was an accomplished musician who had only recently moved to Trivandrum city. She lived with her teenage son, Hari on the second floor of Paradise Apartments. The main living space also served as an ornate music room: a multicoloured jamakalam covered the mosaic floor; rich Tanjore paintings of gods and goddesses adorned the walls and several perfectly tuned instruments lay in the room, waiting to come to life.

Lavanya thought her music teacher dazzled like a Tanjore goddess herself, dressed in a Kanchipuram silk sari with diamonds glittering in her ear and nose rings as she started the first music lesson with a small prayer. She stared in awe as her father made the necessary introductions. Saraswathy Aunty taught Lavanya how to hold the Veena from below, covering the frets with her left hand, while plucking the strings with her right hand. “Sa..Pa..Sa..” she played first, setting the tone before the lesson.

The music lessons were scheduled for Wednesday afternoons, after school. Lavanya changed out of her school uniform and into her pavadai before setting off by the lotus pond towards Paradise Apartments, with her father, wondering what colour sari Saraswathy Aunty would wear that day.

In the first few weeks, Saraswathy Aunty taught her the basic elements of musical structure; “Shruthi is the pitch, Raga is the melody and Tala is the rhythm,” she said sitting cross legged on the floor, her large expressive eyes, boring into Lavanya’s shy ones. Every lesson was first rendered vocally and then repeated on the Veena. In the next few weeks, Lavanya mastered all the musical exercises and even learned a few small songs as well. Before long, her small fingers were running over the frets effortlessly.

The apartment always smelled of freshly brewed filter coffee and hot Tiffin, with an undertone of heady jasmine. Some afternoons, Hari sat at the dining table in the adjoining room, his nose buried in a medical textbook. He only looked up to savour the spicy Tiffin or listen to his mother start a new lesson. “Hmmmmm..,” Saraswathy Aunty’s deep voice resonated, as she set the Raga for the day.

Saraswathy Aunty strictly adhered to the customary rules of teaching Carnatic music. She sometimes took a break to give her pupils a brief history of the composers and their work. She was an excellent story teller; her bangles tinkled and her fair face became animated. Lavanya loved these afternoons; an escape into the courts of the Kings of the Vijayanagar Empire. She listened, mesmerized by the language and culture of a lost kingdom. Her father too seemed transfixed in his escape into the bygone era.

Sometimes, Lavanya gave up a game of hide and seek or hopscotch with her friends to stay indoors and play songs on her Veena. The mellow, tonal quality of its music made her remember her mother. She imagined her mother to have a pretty face, dancing kohl lined eyes and a long braid, playing lovely tunes on the Veena.

There were no photographs of her mother in the house; Lavanya wondered if her father missed her at all. He had begun to spend the twilight hours of each day in his armchair, staring out onto the lotus pond, with a glass of whisky in one hand. He seemed depressed and his work suffered. He rarely left the armchair to listen to her play or accompany her to the music class. She began to notice subtle changes in his behaviour; he seemed a little evasive and avoided eye contact with her. Then there were the women; Pillai Uncle’s relatives, he told her. But they always seemed to leave before she came home from school, leaving a trail of jasmine buds on the crumpled four poster bed.

Seeking refuge from her life at home, Lavanya’s visits to Saraswathy Aunty’s flat became more frequent; she felt comforted by the soothing music amidst the glittering Tanjore paintings. She watched her music teacher conduct lessons for other pupils, long after hers and lingered on to help with the daily chores. She even accompanied Saraswathy Aunty on her family outings to the temple or the outdoor flower market. She became so close to Saraswathy Aunty that she did not mind when her father took up a bank job in Dubai, leaving her in the care of her grandparents. She barely missed him.

“You know, I feel delicate to keep telling you to practice more and more,” said Saraswathy Aunty, one day. The diamonds in her ears and nose caught the slant afternoon light. They were playing a complex composition, a Keerthana in Sree Raga. “I want you to play at the Music Festival in the temple in a few months and you are not ready,” she continued firmly.

Sitting cross legged in front of her, Lavanya nodded earnestly. Her pigtails tugged at her head and the recently tightened braces pulled uncomfortably at her teeth. “You must feel the raga and tala inside. Let’s start again,” said Saraswathy Aunty, a little vexed. Pursing her lips, Lavanya ran the fingers of her nervous left hand over the frets one more time to bring the melodious Sree Raga to life.

A plan for a new three storied mansion was not the gift Lavanya expected when her father finally returned from Dubai five years later, with his newly acquired fortune. “We are going to tear this old Nalukettu house down,” he told her and Lavanya had run back to her music teacher’s flat. “I love the Nalukettu house. It was my mother’s,” she thought, panting. Flushed and confused, she had waited in Saraswathy Aunty’s house, for the music to still her.

Lavanya found refuge in the library room of the newly built house, but she missed the smells of the Nalukettu house and airy space of the central courtyard. Her father, however seemed less pensive; the change had been good for him and the veranda was empty at twilight.

“Let us have an outdoor lesson,” Saraswathy Aunty told Lavanya one day. They left before dawn the next morning. The Arabian Sea shimmered in the clear morning light. “Like the sea, Ragas too can evoke emotions. Hmm..Hamsadhwani evokes happiness; Bhairavi evokes romance.. But what do you know,” she was saying. Lavanya tasted the salty wind on her face, chased the gentle waves with Hari and walked around in the sand looking for shells. “Saveri evokes sadness,” Saraswathy Aunty was saying, but Lavanya was running her fingers over the bumpy green surface of a beautiful beaded conch shell. “I will make a wish,” said Saraswathy Aunty closing her eyes and clutching the shell to her chest. “What is it?” asked Lavanya. “Hmmm..Win a prize at the music festival, and I will tell you,” said Saraswathy Aunty.

The Carnatic Music Festival, held annually in Trivandrum was one of the most prestigious music festivals in the country. Even Saraswathy Aunty had made her debut here. And now, she had chosen Lavanya this year to represent her. “How thrilling,” thought Lavanya, colouring at the prospect of sharing a stage with the maestros.

Walking home from the music lesson, Lavanya studied the calluses on the fingers of her left hand. She vowed to practice hard and make Saraswathy Aunty proud.

Music appreciation came naturally to Lavanya as she sought to portray the spectrum of emotions and colours of each raga or tala in her playing. She began to build up the unique mood of each raga and tala as she rehearsed every day. She even began to hear music in the humdrum of everyday life: in the gentle rain, in the twittering of little birds and sometimes even in the noisy playground in school.

In the next few months, Lavanya practiced her music till it became a part of her. In the meantime, however, her father had slipped back to his old ways and the unwelcome visitors once again came and went before she got home from school. But Lavanya knew she had to focus on her music till she knew where she was and what came next on the musical map.

Till that day.

The day of festival had finally arrived.

Lavanya hurried home from school earlier than usual to ready herself for the performance. Hearing voices coming from her father’s room, she ducked into the library to avoid the unwelcome woman visitor. Through the half open door, she saw the back of her beloved music teacher; her lovely deep red sari with gold border; lovely jasmine buds surrounding her hair bun. Saraswathy Aunty was talking in hushed whispers to her father, who was sitting on the crumpled bed. And his eyes: sad, searching, apologetic.

Stunned, Lavanya sat down on the swing in disbelief.

The temple at dusk looked magical. The outer wall was lit by many tiers of small oil lamps. A small, neat stage with a microphone had been rigged up in the cool interior of the temple.

Music enthusiasts from all over the country had gathered at Trivandrum’s famous Padmanabhaswamy temple, for the annual Carnatic Music Festival. It was considered a great honour to perform during this festival; a platform for many an established musician and also young talent.

Lavanya was led to the centre of this stage, where her Veena awaited her. She sat down cross legged and positioned the revered instrument in front of her. She looked out into the darkened hall; there were rows and rows of folding chairs for seating the guests. Seated in the front row was her beloved music teacher, Saraswathy Aunty looking resplendent in a red silk sari. Her diamonds shone anticipation.

Silence fell; the oil wicks burned; and the audience waited.

“How could she?” she thought. Not her. Lavanya felt her fingers freeze; paralyze with fear. Her heart pounded with anxiety. Her mouth went dry. She ran out, to the murmurs of the audience.

Alone backstage Lavanya panted. She was filled with despair at her failure to perform. She felt confused and dejected; she felt that Saraswathy Aunty had let her down. The audience would think less of her and her friends would desert her. She talked to no one about the silent terrors that took hold of her.

So intense was her shame and embarrassment that she felt that she could not face Saraswathy Aunty again.

Holding her father responsible for her failure, Lavanya’s resentment towards him grew. She became quiet and sullen, without the music to calm her. Her father found that he could no longer care for her, and before long she was with her grandparents in Chennai. When she came back to Trivandrum several years later for a brief visit during the summer break, she found that the once familiar neighbourhood also changed: the canopy around St. Mary’s Lane grew; now Paradise Apartments was hidden from view and new kids played in the badminton court.

When Lavanya turned twenty two, she moved to England to pursue a Ph.D. The bouts of anxiety would reoccur unexpectedly at critical moments, even at her dissertation. She sought help. “Practice music or whatever you are passionate about and visualize that peaceful place,” her therapist advised her gently. But Lavanya could not find that place.

Now back in Trivandrum, in St. Mary’s Lane, Lavanya remembered the times when she was most happy as a child. Seeing the Veena resting among the gods and goddesses in the pooja room, she felt an urge to hear the resonant sounds of its strings. She had missed the sensation of being with the music, weightless, soaring like a bird. She had missed that peaceful place.

Lavanya ‘s thoughts went back to that fateful day: Saraswathy Aunty; the red silk sari she wore the last time she saw her. What happened that evening hardly mattered now. “I must see her. I must see her,” she resolved as she ran impulsively towards Paradise Apartments, past the badminton players and up the stairs two at a time. “The blue sari. No. The orange sari with the green border,” she speculated, as she waited for the door to open.

Lavanya’s ready smile faded when the door was opened by a portly young man with a thick moustache. It took her a few moments to recognize him. “Hari..?..I’m..,” she began hesitantly. “Lavanya..,” he finished studying her sensitive face and willowy frame. “Come. Come in..,” he offered, stepping back.

The living space no longer bore any resemblance to the old music room. Lavanya’s eyes maundered around the room, taking in the large flat screen television, bulky sofa and strewn toys before settling on the young woman who had walked in with a baby on her hip. Lavanya smiled enquiringly. “My family,” said Hari as an awkward pause ensued. “Saraswathy Aunty..?,” said Lavanya finally breaking the silence. “I will take her,” said the woman leading Lavanya through to the room at the end of the hall.

It was the orange sari with the green border; crumpled and draped around a frail older woman, lying on a cot. Lavanya could barely recognize her as the Saraswathy Aunty that she once knew and admired. The light had somehow dimmed in the large expressive eyes and it seemed to Lavanya that even the diamonds had lost their lustre.

The room smelled of Dettol; bottles of medicines lay on the bedside table. The Tanjore paintings that once gleamed proudly now lay in a stack in the corner on the jamakalam. Saraswathy Aunty’s antique Veena lay beside them, lifeless and silent.

“It is you,” said Saraswathy Aunty, when Lavanya sat down on the bed beside her music teacher. “Lavanya…Lavanya..” she said, gathering Lavanya’s slender fingers into her callused hands. “Only you could play the Sree Raga so well. It is in my head now. Play it for me,” she said. Lavanya searched her music teacher’s tired face for an explanation. Saraswathy Aunty reached under the pillow and drew out the beaded conch shell. “We never finished the outdoor lesson on the beach all those years ago. The Raga Sahana evokes inner peace. I wished that you would seek solace in music. I even went to talk to your father about it on the day of the music festival,” she said.

“And my wish was to win a prize at the music festival,” said Lavanya meeting Saraswathy Aunty’s eyes. She then stood up and opened the windows in the room. Streams of dusty afternoon light spilled into the room, illuminating Saraswathy Aunty’s face, and catching the sparkle in her diamond nose ring.

“I must start at the beginning,” she thought, seating herself on the old jamakalam. She smiled at her music teacher and set about turning the tuning pegs on the side of the instrument.

Rama Shivakumar is a short story writer who has published her work in numerous literary journals and magazines including, Muse India, Cerebration, Word Masala, Indian Ruminations, Asia Writes, Reading Hour and Pyrta. Her children’s stories have appeared in Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan’s journal, Dimdima. Some of her work has also been featured in the anthology entitled Celebrating India, published in 2012, by Nivasini Publishers. Hailing from Bangalore, Rama now lives in Bethesda, Maryland with her husband and seven year old daughter. She works as a scientist in a biotechnology firm and has participated in workshops at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda.

Leave a Reply