Since the publication of Naazmaa (1985), his first ever collection of Assamese poems, Anubhav Tulasi has made a lot of experiments with the forms of his poetry, and at the same time he has expanded the range of his subject matters and themes. He has explored the resources of the Assamese language and exploited them to create his personal idiom in his poetry. Today Anubhav Tulasi is a distinctive voice in Assamese literature frequently heard in the Indian poetic scene. He is richly endowed with imagination, and his poetry at its best is refreshing, evocative and suggestive. He is not that sort of poet who has shown a penchant for playing to the gallery. The real forte of Tulasi as a poet is his personal feelings – intense and subtle, immensely varied and very personal. Yet his poetry is so rooted in Assamese culture and ecology that some of his very fine Assamese poems defy our best attempt to translate them into English.

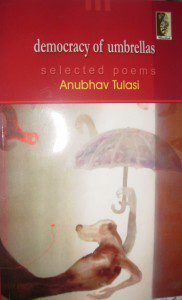

Democracy of Umbrellas, a collection of selected poems of Anubhav Tulasi, is an attempt to introduce the Assamese poet to readers at the national and the international level. Forty-eight poems have been picked and chosen on the basis of their subject matters and themes. The poems are grouped according to their relatedness to some broad theme such as the landscape/ecology, folklore, and culture of Assam (pp 1–9); pangs of love and sadness (pp 10–17); poetry and poets (pp 18–24); politics, angst, violence, nightmare, dilemma of common people (pp 25–39); poems of ideas (pp 40–48); relations (pp 49–52); celebration of life (pp 53–60) and a travel poem (pp 61–63).

As a child Anubhav Tulasi grew up in a village whose landscape and culture nourished his poetic sensibility. His response to nature and its seasonal changes find eloquent expressions in ‘Pied autumn’, ‘Spring comes playing the flute’, ‘Again on Saturday’, ‘Monsoon-hued body’ and so on. Steeped in Assamese culture, the poem ‘On the night deepened by pigeon’s coos’ expresses this pangs of love and anxiety of the speaker. In ‘Bamboo leaf’ and “Roots of the Sonai’, readers will hardly miss Tulasi’s close observation of nature and the solitude of woods. From Assamese folklore, Tulasi picked up ‘Panesoi’ a girl who is desired by her step-brother. Tulasi has used a few images which are fresh, vivid and loaded with rural connotations:

During springtime worries grow

Like paddy seedlings stored in wicker baskets

(‘Blood-surged tide’)

a full byre of ambitions will climb up the hill

(‘Again on Saturday the flood will rush around’)

Flesh and blood will crumble in erosion

(‘Again on Saturday the flood will rush around’)

Tulasi’s love poems (‘A magician who first brought love’, ‘Rain’ ‘White-clad’, ‘Roivat’, and ‘Madam’s eyes’) have captured the pangs of love with poignancy. They evoke a trail of profound sadness with fresh and striking images and metaphors:

That day

On a curved knife

I was scaling

The live fish of life

(‘A magician who first brought love’)

In ‘Roivat’ the poet has captured the tension between the ecstasy and inhibition of the lover/speaker. Tulasi is used to reticence rather than declamation, and he can work his magic on quietness. Silence waxes more eloquent in ‘White-clad’ and ‘Moving house for the fourth time’. In ‘Madam’s eyes’, the speaker, a married man who falls in love with Madam’s eyes, is torn between two conflicting emotions. But at the end he makes up his mind to keep the pair of blue eyes with all his woes.

The creation of poetry is a mysterious process – precisely that is the subject matter of the poem ‘At midnight to the poet’s home’. In ‘Who would ever care about poets’, Tulasi pays his tributes to two great international poets – Tu Fu and Anna Akhmatova, whom he has passionately read. (Indeed, Tulasi has translated Akhmatova into Assamese). But he is modest about his own poetry; in ‘The best poem’ the speaker’s self-mocking tone is unmistakable. ‘The column of poetry’ and ‘Inauguration of a new collection of poems’ are laced with satire.

The title poem of this collection ‘Democracy of umbrellas’ leads the largest group of poems (22–32) that reflect the present reality against a backdrop of globalization. Murky politics, violence, consumerism, erosion of human values – all this results in the dilemma, angst, nightmare of common people, who are being treated as ‘piles of petals of Indian corals / lying on grounds’. Tulasi’s poetry exposes with sarcasm the rapacity of modern man who is willing to exchange his wife for crisp dollars of foreign traders (‘Malaise’). His poetic sensibility has captured with telling effect the nightmares of the present society living through violence (‘The garden of spring’, ‘Smiles on the faces in hoardings’, ‘Birthmark’). No Assamese poet has better captured the angst and dilemma of the ordinary person with poignant satire than Tulasi does in ‘I won’t go shopping but go’. When it comes to the crunch, the speaker, an ordinary person, is simply unable to take the right decision:

Meaning to buy a bouquet of flowers

I buy dodders

Meaning to buy bulletproof

I buy the white of a shroud

‘Dreams’, an experimental poem, satirizes the political power games through the metonymy of ‘chair and table’. In the political game, pawns may be condemned or resurrected depending on their roles perceived by partisans (‘Nails’). In such a hellish atmosphere every one suffers, but the persona in ‘Infernal Playground’ has the guts to ask:

Is there no way out of this hell

Are we to rot here without protest

because his belief in life is unshakable:

I deep my pen in those flames

And revive the dying breath of the teak leaves.

Poems 33–40 grapple with ideas – absurd ideas of compiling a weird dictionary, building a castle in the air, living the life of a headless one, the metamorphosis into a bird, the dearth of Dearth and so on. Here the tone of the speaker is serious; the mood is pensive though not without the touch of satire in places. Among these complex ideas, there is the unexpected flash of self-realization. Tulasi defamiliarizes ordinary insignificant things into a sudden realization:

Whose is this face

ever seen

ever pale

Say O mirror

(Ever seen)

The theme of ‘Canine’ is an irritation which has nagged the speaker for a pretty long time. The speaker is vague, and he cannot trace it back to a single source.

‘Birdman’, ‘A star up above’, and ‘Aunt’ are poems of relationship. In ‘Birdman’, a touchy poem, the speaker’s mother develops an intimacy with Birdman, which her husband approves of, to the embarrassment of the ‘blossoming young sisters’ and the speaker himself. The poignancy of ‘A star up above’ is due to the way the speaker narrates the death of his father with vivid striking images and genuine feelings.

Anubhav Tulasi celebrates life in the poems ‘Celebration of a rare evening’, ‘Dance of the mantis’, ‘Fishes’ and ‘The prodigal’. The dare-devil persona in ‘The Prodigal’, which has the allusion to the biblical story of the prodigal son, learns the hard lessons through his harrowing experiences, defeat and self-realization and returns to the traditional way of life:

to my old house

….

to the sombre beat

of the prayer-hall’s drum

‘Hydera Diary’ is not only a travel poem – it’s a celebration of life.

It is really challenging to capture the charm and music of Tulasi’s Assamese poems; some of it may be lost in English translations. But semantically the poems in this collection are very close to the originals. The very intensity of Tulasi’s feelings makes his language palpable and concrete, despite the collocational differences between Assamese and English. His images, metaphors, symbols are vivid, sharply drawn and pregnant with nuances. It is the subtle variation of his tones that makes the poems of Tulasi a pleasant read.

About the Poet : In his own words, Anubhav Tulasi, is “relentless in fighting a crusade for the freedom of the writer and the written word. For (him) a word originates in silence and to it ultimately the word must return. He has over seventeen books to his credit…He adds “poetry has been a continuous struggle for me and will remain so…”

About the Poet : In his own words, Anubhav Tulasi, is “relentless in fighting a crusade for the freedom of the writer and the written word. For (him) a word originates in silence and to it ultimately the word must return. He has over seventeen books to his credit…He adds “poetry has been a continuous struggle for me and will remain so…”Editors : Nirendra Nath Thakuria and Anubhav Tulasi

Translators : Hiren Gohain, Pradip Acharya, Ananda Barmudoi, Krishna Dulal Barua, Nirendra Nath Thakuria and Anubhav Tulasi

Anubhav Tulasi is a front-runner of modern poetry in Assamese, a bilingual critic, essay writer, editor, and translator.He is also a crusader for secular anti-caste views, causes like environment, human rights. He is a well known speaker on issues concerning contemporary Indian literature and culture

Leave a Reply