so beautiful,

you’ll wake up crying!”

—Michel Faudet

Mr. Basu Ray had been twisting the channel knob of the nineteen inch black and white television set in his living room, when his eye fell on the little patch of green outside his house. A stray dog had walked into the premises and was now sniffing at the bed of roses he had painstakingly brought to life with ample doses of tea leaves and long hours of garden toil in the sun. Gnashing his false set of teeth, Mr. Basu Ray grabbed hold of his late father’s walking stick and rushed out of the house to tackle the unruly quadruped.

The animal, being well-equipped with that strong sense of premonition that comes from a lifelong practice of evacuating its presence in quicksteps when confronting little boys armed with bricks and stones, knew that danger lurked on the horizon as soon as it saw Mr. Basu Ray’s rotund figure equipped with a walking stick coming in its direction. It wasted no time sniffing at the juicy pink roses anymore, and took its exit as fast as it could.

This untimely exertion of chasing dogs out of his grounds got Mr. Basu Ray puffing; so, after latching the iron-gate in the garden that the stupid maid had as usual forgot to fasten when she left, Mr. Basu Ray stood for a minute wiping the sweat that had gathered on his forehead with a cotton handkerchief. Still breathing heavily, he then turned in the direction of the house; and having caught sight of a yellow-beaked Shalik pakhi perching atop the television antenna, he stood for a moment wondering if the bird was in any way responsible for the bad signal his television set received. Exculpating the bird with a sigh, he turned his attention to the house with a paint-crumbling exterior and a grimacing brick-teethed visage that stood before him.

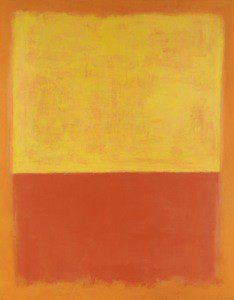

Under the dusk-laden sky which seemed to be a blotchy canvas of some withering talent-less abstract artist, the house looked more weather-beaten than usual. Its once yellow-ochre facade seemed to scream in piteous tone for a lick of paint. The bastard plants born in its many cracks and crevices that adorned the house had disgorged their weedy heads out of their germinating corners and were now in the process of slowly and lingeringly throttling the grey, two-storied citadel.

As Mr. Basu Ray stood inspecting the house, his double-chinned, round, dark face with its little black eyes under bushy eyebrows looked even darker in the shadows. He was a middle-aged man sporting a rotund paunch, common among rice-eating Bengali men, and a receding hairline. A stale scent of pedestrianism wafted from him like the stench of sudoriferous vegetable-peels, egg-shells and fish bones marinating in their own juice in the incarceration of a garbage bag. He wore a pair of ill-fitting trousers and a blue and white striped shirt, which showed off his bulges in his upper and middle frame. His feet encased in heel-holed navy-blue socks were thrust into a pair of once-brown shoes that like the house he was beholding too seemed to cry for a lick of shoe-paint preceded by a thorough brushing off of the dirt and grime.

The tinkling of a cycle bell behind him followed by a sharp pain in his left calf brought him out of his contemplation. Rubbing the pained spot, Mr. Basu Ray saw the little pebble that had hit him. He picked it up and threw it in the direction of the empty street, turned, said “hatochhara bandor!” in a loud voice, and went inside the house.

“Shall I bring you your tea?” Mrs. Basu Ray asked her husband when she saw him coming in. The clock had just struck seven and without answering his wife, Mr. Basu Ray rushed to the television set and turned the channel knob to DD Bangla to watch the evening news bulletin. “Ki go, shall I bring you your tea?” asked Nirupama Basu Ray once again. “It’s terribly warm today,” she continued rubbing the sweat from her dry-skinned, wrinkled, oval-face with liver patches with the edge of her red and blue floral patterned cotton sari. “I wish we could install an AC like the Mukherjees.”

“Why do you always keep talking about others,” yelled Mr. Basu Ray momentarily turning to his wife and then turning to the television set once again and slapping its back a couple of times to adjust the picture. “Can’t you be happy with what you have, woman? Always talking about others, always. The Mukherjees have money and we don’t.”

“They also have two daughters and a son, and still they could afford an air condition,” said his wife scratching a mosquito bitten spot on her unshaven arm.

“Well, it seems that they can but I cannot; and I can’t help it,” retorted Mr. Basu Ray retiring to the sofa covered with an old green towel when the TV screen after numerous slaps finally displayed a well-bred sumptuous Bengali woman in spectacles speaking in a somber tone the bisesh, bisesh khobor of the day.

“Get me my tea,” he said with his eyes fixed on the television set. His wife sighed and turned to the kitchen. “And, oh, yes,” she heard her husband add, “don’t put any milk and sugar in it.” His wife smiled. The weather bulletin announced a chance of heavy rainfall in Kolkata and its neighboring areas.

The weatherman at the meteorological department in Kolkata was a person whose climate-clairvoyance generally vacillated between two sharp binary boundaries: correct and incorrect. Were you a betting person, and had wagered a considerable sum in favor of his prophesy, the chance of your losing the cash-slab would be gravely affirmative; but today, unlike other days, his crystal ball had prophesized the weather conditions absolutely correctly. Around nine in the evening when Mr. Basu Ray was kneading the chapatti dough, he heard the thunder grumbling outside his kitchen window. By this time coiling, grey, intestinal cloud had started to gather in ample profusion in the abstract artist’s canvas abaft. It wasn’t raining yet, but Mr. Basu Ray sensed a refreshing smell of wet grass in the air. Seeing the milk saucer containing the refreshment he had offered to the cat in the afternoon still untouched, he craned his neck and spoke to his wife who had been sitting in the towel-covered sofa reading Sukhi Grihokon, “Have you seen Neelkomol?”

“No,” she replied. “Are you done? It’s getting late.”

“Wait for another ten minutes,” Mr. Basu Ray said rolling out the dough. A homeopathic doctor, he thought, I will show her!

In exactly ten minutes he finished cooking his chapattis, and though none of them puffed the way his wife’s chapattis did, he thought he was doing a great job. Indeed, he was willing to make some concession for his own safety. Boiled milk and chapattis cooked by himself seemed to be the safest bet. Discarding the edges of his chapattis and pouring a dollop of jaggery in his milk he came out of the kitchen. “I am done,” he said to his wife placing his food on the plastic covered table.

Around midnight, the rain came down noisily in torrents. It was as if a million angry gods were micturating on a city they despised. Thunder like the malicious eructation of some sky-dwelling monster created an awful syncopation along with the rain and the frequent ianthine luminescence of lightening that Mr. Basu Ray hardly found somniferous. The figure next to him sleeping with her mouth open seemed to be unperturbed by the weather outside; and so was the cat lying curled up at Mr. Basu Ray’s feet. He picked it up and it gave out a sleepy meow. “Are you sleepy, Neelkomol, are you sleepy,” he said tickling its tummy. The cat gave out another sleepy meow and Mr. Basu Ray let it rest. A strong urge to hug the woman sleeping beside him arose, but he dismissed it as a reckless desire of a sleepless night. He tried to remember those sudden stomach aches. Oh, yes, those stomach aches; it was that together with the muffled hints and warnings the doctor issued that had alerted him. He had tried to reason with himself, he could not believe his own suspicions. But there was no other way; he never ate anything apart from her cooking. And she was a doctor too, more a quack to Mr. Basu Ray, actually; nevertheless, a doctor, be it a quack Homeopathic physician who gave up her practice upon marrying him because he didn’t like his wife touching and checking random male patients. Mr. Basu Ray wondered if she remembered the names of the medicines she used to prescribe to her patients; but people don’t forget such things as medicine names crammed assiduously into the system by endless hours of memory and recall. No, he was sure, she remembered them all. And even though Mr. Basu Ray had always been dubious about the efficacy of homeopathic sugar globules dipped in spirit, he knew that a large dose of some vitriol that they use, or, say, a small dose of the same administered daily could produce the desired results. He knew it was a smart move on his behalf never to confide in her and declare like the other wife-hugging pansies he knew his actual salary or his cash savings in the bank. But he was sure that she could guess. She was a smart woman, an ingenious one actually. Why did she have a locker to store her wedding jewelry in that same bank? And the idiot of a manager, how friendly he was to his boudi; asun boudi, bosun boudi… huh, that fool! He was sure he had told her. And what a lot of jewelry she possessed, and never did she give one of those tokens, not even one nose pin, to her husband. She had even hid the keys to the locker. A sudden thunderous belch startled him out of his contemplation. His heart had begun to beat. His mind was telling him that he must not delay, he must not delay. He must get it over and done with quickly. The house that evening had looked more awful than before. It was a sign to hurry things up. Vacillating won’t help, he had to be a man, and a man he was. Another thunderous clap issued from the sky and Mr. Basu Ray got up from his bed and started pacing up and down the dark room.

Mr. Basu Ray’s mind was a cesspool of thoughts each erumpent with unheeded possibility. Like the holy Ganga that night, which was acting as the jorum to the regurgitated slime of the city holding in her bosom its dead dogs and cats, its plastic packets and discarded mineral water bottles crushed by unknown feet, its excrement laden street grime, and other quisquilie that had danced their way into its watery womb under the force of the rainwater, Mr. Basu Ray’s mind too was a grime-thick chamber heavy with obnoxious fumes. He was still finding it difficult to come to terms with the fact that he, Mr. Basu Ray, a gentleman, a true-blue bhodrolok, if there was one, could have such an idea. It just shows you how utterly and inexplicably complex the human mind is. When he was little, his grandmother, a widowed octogenarian with almost opaque spectacles, used to tell him about the story of the goddess Durga slaying the green demon, Mahisasura. When narrating that tale over and over again, his grandmother would talk more about the slain demon and how he was avenging the death of his father, Rambhasura, the erstwhile king of the demons, at the hands of Indra, the king of the gods. The more Mr. Basu Ray would ask her to talk about the goddess and how she had slain the asura, the more his grandmother would digress and talk about the poor Mahisasura and his piteous plight. She used to say to him that nothing in the world is good or evil; it is just a point of view.

Thinking about his grandmother now assuring him with a toothless smile that it was all right to think the way he did, Mr. Basu Ray felt composure dawning on him. Of course, he thought, his slippers flip-flopping as he moved up and down the room, it was the only logical thing to do after all. Therefore, pulling out the thought from behind the dump of forgotten faces of acquaintances, incidents of youthful sexual deviancy that now embarrassed him, unfulfilled dreams and career aspirations, and many more memories he had hoarded over the years in his mental chamber, he decided to face it squarely.

The hands on his steel-band Citizen watch with glow-in-the-dark stickers on them announced that it was nearly two in the morning; nevertheless, Mr. Basu Ray found it impossible to get back to bed. The spirit of the stormy night was up and about in him. He continued pacing up and down the room and gazing at his wife’s sleeping frame from time to time. It was just like that stormy night when the plan first came to his mind. He was suffering from one of his temperamental stomach aching fits and writhing with pain. He remembered she was sitting in the living room at the time watching an Uttam-Suchitra flick. The hero with smartly brushed air was singing Ei poth jodi na sesh hoy, tobe kamon hoto tumi bolo to? Listening to that famous tune in conjunction with the noise of the rain, Mr. Basu Ray had felt the pangs of pain hitting him more strongly than ever. It was at that moment, at precisely that moment, when he was throwing his limbs about in pain and cursing the doctor when the idea manifested in his mind. The unrelated spark of that idea illuminated his musty interior. And, quite rashly, he now felt, no sooner had he thought of it, he had shoved it, like a dog hiding its bone, beneath blankets of past regrets too ashamed to even consider its efficacy before jettisoning it for good only to retrieve it the following day when the light of dawn had clarified his boggled mind.

A fortnight had now elapsed between the inception of the idea and Mr. Basu Ray’s ultimate approval of it. Right now, the movie of the mind was starting once again to feature itself like every other day on the silver screen of his mind. By now, he had grown accustomed to the thought being there, inside him, gradually inflating with purpose everyday like a child in a mother’s womb. He did not dismiss it any longer as an aberration of the brain caused by the pangs of pain. And tonight, when he unhesitantly acknowledged its presence, he knew he wasn’t ashamed of it anymore. Dipped into the chemical bath of the stormy, stolid night, the photograph of the mind came into being.

As he watched the feature film playing on his mind, Mr. Basu Ray thought, it was a great move of his barring the house to the chatty Mrs. Mukherjee and Mrs. Biswas; what gossips they spread! She had shown her wound marks to them and they had the audacity to come to ask him to control his temper or else they said they would call the police. Control his temper, dash it! He had ticked them off quite well, declaring it was his house and what he did inside his premises was his own business. It rarely happened nowadays, but that didn’t stop the stupid woman from going about the neighborhood complaining about him like a child. Now, she couldn’t communicate with anybody even if she wanted to. No gossip for you, madam. The phone connection was out of order too, and he had meant it to remain that way until he was ready to put his plan to test. You can’t be too careful after all.

For the next few days Mr. Basu Ray played and replayed the plan in his head. Sitting at his office desk and nibbling at his pencil, he thought how good the idea looked. He would tell his wife that an emergency telegram had arrived beckoning him to the village. Perhaps old Pisomosai would be ill; he would possibly be in his death bed. He would then pack his things and leave the house in the evening. Of course, the timing should be right; the maid must see him leave, or, better still, he must leave just before she had left. He would then go to the railway station. It would be great if he could meet some of the local nibs on his way; perhaps, he could greet Mr. Biswas or Mr. Mukherjee; but he wasn’t sure if they would entertain him considering he had insulted their wives. Mr. Basu Ray clicked his tongue. Anyway, he continued, he would procure a couple of tickets for the Shantinagar passenger. The station would be crowded and nobody would notice if he at all boarded the train. He would then choose a corner in the station, preferably near the loo where nobody went, and wait. Around midnight he would come back home through the backdoor in the bathroom and switch on the gas. He would then pour the kerosene on the shabby sofa and the other furniture— he had two full jars of the blue liquid issued from the ration shop nestling in the house—and then it would take just a flick of the match to do the trick. He would light it just before closing the back door and leaving the house. If it rained, he must be cautious about the footprints; but he couldn’t predict that now. All he could see was her engulfed by the flames. A fit justice, Mr.Basu Ray thought, for a woman poisoning her husband.

Of course, before anything was done, he would have to administer the sleeping draft. It would be easy; it would just take a sleight of hand to add the potion to her sugared evening tea. After he had performed his final task that night, he would take the back alley and go back to the station and wait there among the sleeping beggars and the fruit-vendors for the first train. He must be in the village home before morning so that everybody would think he had come the day before. That wouldn’t be difficult considering the village was just a few hours from Kolkata. He must walk from the station too through the bamboo forest lest somebody should see him coming. He would talk to Pisomohai early in the morning, and that would give him a nice alibi when the news arrived. He would of course play the role of a bereaving husband on hearing the news that his wife had decided to end her life. He still retained some of those amateur theatrical skills he had learned as a young man. Finally, after a month’s hiatus, when all the dust would settle, he would visit the city and approach the bank with a request to empty the jewelry locker. The gold rate being still very steep, he would probably make a packet.

In an effort to make the last few days of his wife’s life happy, Mr. Basu Ray got her the air condition, although a third-hand one, she had always wanted. Twice, he took her to the movies too; and, on the day before his plan would be set to action, which was their twenty-fourth wedding anniversary, he let her feed him too. It was all he could do to make her happy before he ended her life. To celebrate their anniversary, he got her twelve sticks of Rajnigandha and a Hilsa fish for dinner. She cooked the fish in a savory mustard sauce and served it with warm Basmati rice. She dressed up too for him too that evening wearing the teal colored boubhat Banarasi sari with her gold choker necklace. Mr. Basu Ray eyed the choker for sometime; he had no idea she had jewelry kept in the house. He decided to make a thorough search when she went for her bath the following morning. Who would guess, Mr. Basu Ray thought, looking at her as she placed the warm plate of rice and fish before him, that she wished her husband’s death.

When Mr. Basu Ray retired for the night after his sumptuous anniversary meal, he felt both tired and relieved. A new thought now played in his mind. It came as he was eating the Hilsa, the first time in the season actually. Savoring the fish with closed eyes, Mr. Basu Ray felt that he ought to stretch a point. “The fish tasted magnificent,” he said to his wife as she was clearing the table.

“You really think so?” she asked.

“Yes, shotti, it was very good. I didn’t believe the fishmonger when he said it came from the Padma; but I think it did. I hadn’t had such a good Hilsa in a long time,” he said with a sigh. “Aren’t you going to have any?” he asked seeing his wife was eating a plate of rice with milk.

“Oh, I can’t have Hilsa in the night; it’s too heavy. I will have it tomorrow for lunch. I saved another piece for you too,” she said with a smile. Poor woman, Mr. Basu Ray thought, looking at his wife’s face, perhaps he had been a little too hard on her. The benevolence that had manifested on the surface of his mind like a corpse rising up on the face of a pond where it had drowned several days back, asked him to consider his decision. He knew he was a good man at heart; after all he belonged to a spiritual family, where from childhood up he had been taught to respect and follow the ideals of ahimsa and forgiveness. He murmured to himself his grandfather’s favorite lines by Swami Vivekananda:

“Bahuruphe Sammukhe Tomar Chari Khotha Khujisho Iswara,

Jibe Prem Kore Jei Jon Sei Jon Shebiche Iswara.”

His stomach didn’t ache that night after the meal; rather, he felt unusually fit after the hearty after dinner. In any case, as he rested his head on the pillow and looked at his wife undressing before him, he felt he needed some more time before he reached a final decision.

Mr. Basu Ray did not know how long he had slept before waking up with a start feeling suddenly very warm and thirsty. A horrid sweltering stench from the twisting and coiling miasma that had filled the room as he slept burned his nostrils and made him cough violently. Smoke danced before him like ectoplasm gathering form and shutting-close all view. For a few seconds, Mr. Basu Ray sat on his bed coughing, his sleep-fogged brain unable to register what was happening around him. He extended his arm to wake up his wife; but the place next to him had not been slept in. A loud crash sounded downstairs. Mr. Basu Ray shot out of his bed, his mouth a desert, his chest abluted with sweat. He gulped. “Nirupama,” he cried out, “Nirupama…Nirupama,” No answer came for him. The radiant heat coming from the steadily spreading orange-yellow flames downstairs was unbearable. Another crash sounded downstairs followed by a loud thud. Mr. Basu Ray rushed to the bathroom. The faucet issued a hissing sound and no water dropped from its spout; the aluminum pail and the mug that rested there had been removed too. His flesh seemed to sizzle in that blazing warmth coming from downstairs. A dizzying vibration sounded in his ear; the booming lub-dub of his cardiac organ was deafening too. Covering his mouth and nostrils, he ran out of the bathroom and observed that tall, fierce, fiery flames had now engulfed the wooden rails of the stairs. Their strange yellow-orange luminescence charged with boiling wrath was spreading about the house with feral fury and seemed to be pulling him to some smoky labyrinth with coiled entails and no exit.

Trembling, Mr. Basu Ray thought about the telephone, yes, the telephone, he must get to it. But he hadn’t had it repaired. Mr. Basu Ray gave out a loud cry, and then another, and another. Smoke and bits of ash burned his eyes. Coughing, he rushed to the windows in his room, but they were latched. Little travel locks descended from them. He had himself had the latches installed. It was just another safety measure he would take to bar her from communicating with strangers. The travel locks were his idea too. He rushed to the dressing table to find the keys, but all the drawers were empty. He shouted as loudly as he could, “Bachao, amae bachao, somebody save me, please.” The Biswas family, next door to him, Mr. Basu Ray remembered, was out on their annual holiday. But, why can’t the Mukherjees hear him? He gave out another yell, but a deafening crash that shook the house muffled his voice. Mr. Basu Ray’s eyes felt heavy, his nostrils burned from the putrid smell of the black sooty smoke. He sat with a thud on the floor. A heavy, murky stifling sensation seemed to be throttling him in that opaque room with its numerous thin, bony fingers. A lump had materialized in his throat. He knew he couldn’t crawl away. He opened his mouth to let out another cry, but his sore and dried throat couldn’t produce any sound. He sat huddled up on the floor in a pool of urine, sweat, saliva and tears listening to the dizzying cricket-noise in his ears together with the crackling, crashing and blistering sound that surrounded him. Placing his cold sweaty palm on his chest to stop the heart from beating so loud, he began to count multiplication tables in his head. Two one is two, two into two is four…

Just before losing consciousness, Mr. Basu Ray remembered seeing through the smoke the obese golden-orange flames closing in on him like a million army men on a single enemy. The heat didn’t bother him anymore, and neither did the sight of the blazing flames or the crashing or splintering, and sizzling noise about him. He felt utterly relaxed and calm. A sigh of relief escaped him as see saw the wild snaky flames of fire reaching for him with the open arms of a loving spouse.

The End

Glossary of Non-English Words:

1. Shalik Pakhi: Common Myna/Indian Myna

2. hatochhara A common swearing word among Bengalis, equivalent to a rascal or a loafer.

3. Bandor: Monkey; used as a swearing word here.

4. Ki go: An informal way Bengali a wife calls her husband.

5. Bisesh, bisesh khobor : The headlines of the day

6. Sukhi Grihokon: Literally, Happy Household; it’s the name of a Bengali magazine for women.

7. boudi; asun, boudi, bosun, boudi… Literally meaning: Please come and a have a seat, boudi. Boudi means sister-in-law; it’s a common way of addressing married women in Bengal.

8. Bhodrolok: Literally gentleman in Bengali.

9. Asura: Demon

10. Ee poth jodi na sesh hoy, tobe kamon hoto tumi bolo to? : Lyrics of a famous Bengali song from the movie Saptapadi starring Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen. The song was performed by Hemanta Mukherjee and Sandhya Mukherjee.

11. Pisomohai: Uncle; husband of father’s sister.

12. Boubhat: Wedding reception

13. Hilsa: A tropical fish especially popular among Bengalis.

14. Shotti: Truth

15. “Bahuruphe Sammukhe tomar Chari Khotha Khujisho Iswara, Jibe Prem Kore Jei Jon Sei Jon Shebiche Iswara.”: A famous quotation by Swami Vivekananda meaning One who have the love and care for all, not only animal but all creature.

16. Bachao, amae bachao: Save me, save me

Indian Literature | Indian Review Author | Barnali Saha. Read the works of Barnali Saha on Indian Review. Visit us and find other amazing authors from India and the world.

Leave a Reply