1.

The guards, not wishing to make any noise, carried two pine chairs all the way from the commissary, set them down outside the prisoner’s cell, and sat on them. Birm and Erko, whose twelve-hour shift began at eight in the morning, had been doing this for more than a week. It was not expressly forbidden to sit down outside the famous prisoner’s cell, though this might only have been because nobody thought a guard would dream of doing such a thing. Birm was pretty sure it was not allowed and had at first refused. He would have preferred to go by the book, or the book as he imagined it (“stand rigidly, keep woolen tunic buttoned up, say nothing, remain expressionless, beat the prisoner at regular intervals”). He was fairly certain that Lieutenant Dirk would not approve of their singing songs like Fat Charlotte, Come On Over and Red Willy with Korbelius, exchanging jokes with him and, above all, asking him questions about Petra Voss. But then Erko, a veteran nine years his senior, had called him a few names. Even as he gave in, Birm had protested. “We’ll catch it.” Erko looked disgusted and mocked him. “Afraid we’ll get chewed out by the Prick or scared that poetry’s contagious?” Sneering, he added, “Or freedom?”

At first, they had stood expressionless, silent, and had delivered occasional light beatings. Then one day the prisoner Korbelius, whose odd name was supposed to be on the lips of people in London and Paris (“Paris,” said Erko yearningly, “just imagine!”) had told them a joke. He didn’t exactly tell it to them, at least not the way men do in bars. He just sat on his cot as usual, calmly, without looking at them, and began to talk.

“About a year after the Revolution a peasant was plowing up a fallow field when he struck a strongbox. When he pried it open, he found it was full of money and jewels. He realized at once that it must have been buried by his landlord, who’d been executed. Even though the peasant only confided the news to his wife, somehow the local Party boss got wind of it and paid the peasant a visit. ‘I’ve heard about your little discovery. You know, I could confiscate it all; it belongs to the State.’ The peasant kept his mouth shut and stared at the official’s shiny boots. ‘But look here, Comrade,’ the representative of the Classless Paradise said with a suave smile as he put his hand on the peasant’s shoulder. ‘What do you say we share the treasure in the true spirit of socialist brotherhood?’ ‘No way,’ the peasant shot back. ‘I want half.’”

Birm certainly didn’t want to laugh. He was pretty sure such a story merited at least a medium-sized beating; but then Erko guffawed and, despite making every effort to master himself, he did too. After that, it was as if they had unbuttoned their tunics halfway down. There was just no going back.

2.

Petra Voss sat upright and tight-lipped at her desk in the interrogation room, “cool as an icicle locked in a refrigerator in the middle of an iceberg,” as Erko once remarked. She never deigned to bandy words, let alone exchange jokes, with guards. She looked as if she’d been inoculated against humor at birth. This impregnable seriousness fortified her superiority and it both pulled Korbelius in and pushed him away. In an essay on horror movies, he had written that fascination is a type of ambivalence, a confederacy of attraction and repulsion. The snake fascinates the terrified rabbit.

Voss wore a white linen blouse under a crisply tailored navy blue suit, one with a skirt that stopped a millimeter above her knee. It was not fetching, also not a uniform though it might as well have been. Yet she was beautiful, truly beautiful, with a beauty like a blow, a gust that forces you backwards. Neither Erko nor Birm had seen Greta Garbo in Ninotchka or they’d have recognized the combination. Yet there were also differences between Petra Voss and Greta Garbo’s stern commissar. Voss was a true believer yet she not a woman to take her ideas at second-hand; moreover, she was no ascetic, at least not intellectually. She had been too well educated. In short, Petra Voss was gorgeous, literate, and devoted—just Korbelius’ type.

It was hardly surprising that Birm was intimidated by Voss, who, it seemed, outranked even the colonel who ran the prison. Yet he felt similarly about Korbelius owing to the glamour of his fame. Erko didn’t care about Korbelius’ fame, but he admired the prisoner’s self-control, his obstinacy, what he had come to think of as his serene unwillingness. He didn’t understand precisely what Korbelius was unwilling to do, say, or write—or not write for that matter—all that went on above the heads of humble screws; he simply respected the way the man resisted. Both guards knew, of course, that Korbelius was a special prisoner. Who else had guards posted outside his cell around the clock? Who else got a cell all to himself, one with a proper toilet? Why the isolation? Perhaps, he thought, it was out of fear that what he’d ironically called Korbelius’ freedom really was catching. “I’ll have to keep a close eye on Birm,” he joked to himself, “or he might come down with a dose.”

“You’re a writer, then?” Erko asked one day, mostly out of boredom.

“Only when I’m writing,” the prisoner replied cheerfully. The man was never sullen.

“Shh,” said Birm, looking down the hallway. Everybody was watched; everybody watched everybody; even guards are guarded.

Erko ignored him. “Well, what do you write then?”

“Words, words, words.”

“Words? What kind of words? Stories? Plays? Movies?”

Korbelius shrugged. “Whatever comes out.”

“And that’s why you’re here?”

“Evidently.”

Now Birm wanted to ask a question too, a practical one. “I don’t get it. If you’re so dangerous why don’t they just shoot you?”

“You’d have to ask them.”

“Come now,” said Erko. “Two sessions a week with the sensational Petra Voss? They want something from you.”

“Perhaps they’d prefer different words. Ones that sound more like theirs. Agreeable words. Stupider ones, I mean. Maybe a live poet who says yes is an asset while a dead poet who says no, isn’t. ”

“Best be careful,” said Birm, frowning. “Don’t get on the wrong side of that Petra Voss. A dead poet wouldn’t faze her.”

“What do you say in there?” Erko wanted to know.

“She says quite a lot. What I generally say is no.”

Birm, again checking the hallway, mumbled, “A woman like that, she could get me to say anything she liked.”

Erko crossed his arms and turned to his partner. “But who would care, you idiot?”

Birm said that a cousin of his, who knows such things, told him that a hullabaloo was being made about Korbelius in the foreign press.

The prisoner shrugged. “Colleague of mine used to say that a country that doesn’t care enough to lock up its poets won’t care about literature either.”

“What a thing to say! Was he ever locked up?”

“Emigrated,” chuckled Korbelius. “To tell the truth, he really wasn’t much of a writer.”

The interrogation room had a different smell from the ammoniac stench of the rest of the prison, as if the air had been scrubbed with bristle brushes.

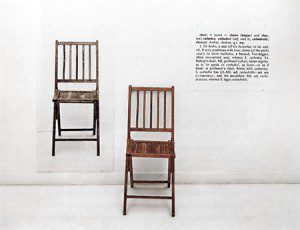

Korbelius stood before the metal desk behind which sat Petra Voss. Erko and Birm reverently closed the door, not a metal door but a regular wooden one, with oiled hinges.

“So here we are again,” said Voss. “Sit down. Please.”

Korbelius seated himself in the hard, undersized chair drawn up before Voss’s desk. His knees were almost even with his chest. Its legs had been cut down so that he would have to look up at the unnaturally dark eyes and marmoreal complexion of Petra Voss. She’ll dominate, he’ll worship—that seemed to be the idea.

She began on a new tack. “They could destroy your reputation, you know. There are plenty of ways. There are crude methods, like the tax charge you’re up on now. Not altogether stupid to make you look mercenary what with all those overseas sales. It’s deplorable but in most of the world, Korbelius, you’re our best known citizen. And what’s even worse, for the moment at least, the most admired.”

Korbelius kept his mouth shut. It was quite marvelous the way his mind started to drift the moment she began speaking to him. The lyrics were derisory but the music enchanting. He found himself wondering if she were married, asking himself why she always said ‘they’ when she really meant ‘we’; then a snatch of unforgotten Yeats drifted across the screen: . . . fit spoil for a centaur drunk with the unmixed wine.

She didn’t slow down. “More subtle would be a charge of plagiarism. It wouldn’t be difficult to arrange. They invent an old novel that happens to have eighty or ninety pages identical to ones in The Avramarash Intervals. Or it might suddenly turn out you’ve been secretly buying up property wherever the next unpopular dam is going up. Or say some letters come to light—from an impeccable source, one of your fervent admirers—in which you call your fellow dissidents credulous fools and proclaim your disdain of the ignorant masses.”

“I never use the word ‘masses,’” he said, mostly just to stop the flow. “And the answer’s still no.”

“No what? No, they wouldn’t dare do such things or no you don’t care if they do?”

“Appearances can be imitated, or fabricated; the truth can’t. You think the world’s always eager to believe the worst.”

“So it is, Korbelius.”

“Then what have you been waiting for?”

“We’re not talking about me.”

“Oh, I beg your fastidious pardon.”

“I prefer a different future for you.”

“No doubt.”

“A better one. Much better.”

“Better for you, perhaps?”

“No, for you. I’ve told you I admire your talent. I want to see you do something constructive with it for a change; that’s all.”

“I’m afraid that would be too expensive. My means are severely limited.”

“Oh, you’re too modest. Your German sales alone—”

“You won’t let me at the royalties.”

“Well, naturally they won’t. Besides, they’d only tax them away.”

“Naturally, you’re opposed to anything royal.”

Petra Voss looked disappointed by his pun. Korbelius enjoyed irritating her with his stubborn, even childish No. She was determined to conduct a dialectic ending with his saying Yes—yes to acknowledging their steps forward, yes to patriotic sentimentality, yes even to renouncing his pen. She wanted to compel him to see that what she represented was positive, progressive, practical, productive, even popular, while he stood for nothing at all, that his stance was merely petulant or worse—romantic. Therefore Petra Voss was not in the least reluctant to argue with him the way wrestlers wrestle. She was sure of her victory; she was practically born debating. His resistance frustrated her as if it were itself no kind of argument at all; as though it were mere pig-headedness.

“This country is large, Korbelius, large and diverse and with a bloody history. It needs a firm hand. Still, that hand has already relaxed its grip considerably; you’ve got to admit that. Bear in mind that the Revolution isn’t even three decades behind us. You undervalue the strides we’ve made. I grant that there were certain unfortunate measures in the early years. Broken eggs, as you called them in that nasty little novella.”

“The Omelet.”

“You’re not a fool. How could it have been otherwise? The country required order, a new system. That firm hand could squeeze but it was nonetheless benevolent. The young are now seizing the bright future that’s been prepared for them.”

“The young? You show them—the most educated—a pair of doors.”

“Doors?”

“One has Money written on it, the other Politics.”

“And they wisely choose the first. You don’t show them enough respect, the young. It isn’t just a matter of wanting to be rich and not, as you would say, free. The young—especially, as you say, the most educated—know perfectly how well the system works and they support it. They prefer it to the alternatives.”

“And if they don’t?”

“Some few don’t, of course. You have some fans among the more unsettled post-adolescents. To them you’re a beacon; you represent the allure of useless, solitary heroism, the head-shaking pose. Like you, these malcontents—most of whom are simply lazy or drunk with Americanization—delude themselves by trying to emulate you. It’s like saying that having epilepsy makes you Dostoyevsky. To them, to insist that freedom’s just a matter of saying no over and over is being like Korbelius.”

“In my present circumstances, that’s just what it is.”

Here Korbelius smiled up at Voss and it was this smile, not what he had just said, that exasperated her. “You say no even to the most reasonable offers.”

“Oh, especially to them.”

Voss tore open the blue folder lying before her on the desk and began to read in a toneless, chilly voice:

“When the iron certainty of fanatics

is fractured by the silken skepticism

of the civilized, when everyone’s rights

are firmly the rights of all, when the dawn

does not disclose a single corpse on the sand

and earthbound hope again extends feathered

wings, then your children may learn to recite

sonnets older and better than this one.

What must we sacrifice to the gods of

weather? Our trucks, our toasters, the Sabbath

lights? In August’s heat, desperate souls dial

down self-defeating air-conditioners.

A tsunami heaves above the supine

land, our delusions of innocence”.

“You read that rather well.”

“Why do you have to write such things?” She scoffed, “Sonnets!”

Korbelius did his best Marlene Dietrich. “Can’t help it.”

Voss closed the blue folder and laid both perfectly manicured hands on top it. “The country is doing well economically. We’re growing more quickly than Britain and twice as fast as France. Exports have doubled in the last decade. The poor are fewer, the rich more numerous every year.”

“So why are you worried about a sonnet?”

“I presume you’ve read Alexis de Tocqueville?”

“Democracy in America?”

“That Tocqueville, not that country. I’m thinking of The Old Regime and The French Revolution. Know it?”

“Where did you go to university?”

“Cambridge. You’ve heard of it?”

She was becoming sarcastic. Korbelius congratulated himself.

“So, Tocqueville, the Frenchman, on the French Revolution. Et ainsi?”

“He has something to say to the point. In that book he introduced the concept of ‘the revolution of rising expectations’; that is to say, the perils of success, success not just in creating wealth but in liberalizing the system, which is what you so relentlessly claim to want—a desire with which I am anything but unsympathetic, as it happens. If you were more honest, you’d admit we’ve been moving down that road.”

“Good for you.”

“But slowly, Korbelius, cautiously, prudently, whereas you’d have us rush headlong right up to the edge of the abyss.”

“Me? Push a whole country? With sonnets and novellas? And into the abyss? Isn’t that a tad overdramatic?”

Voss started to get to her feet, changed her mind. “Tocqueville noted how as soon as the Ancien Regime relieved people from the archaic feudal levies and instituted land reforms they became resentful of every tax that remained, of the order that could have staved off chaos.”

She quoted from memory: “Every abuse that is then eliminated seems to highlight those that remain. .??.??. the evil has decreased, it is true, but the sensitivity is greater.”

“So you want to preserve all the abuses you can?”

“You’re being deliberately obtuse.”

“I’m never deliberate. Too much work.”

“Our problem isn’t the poor. They’re grateful to us. They bow down to us. In France, it was the bourgeoisie who blew things up. Doing well, they wanted to do better. Made freer they wanted more freedom. They wanted everything at once. Well, now we have our own bourgeoisie and, regrettably, some of them read you.”

“Rather than Tocqueville? You sound a bit like the Old Regime yourself.”

“We are the Regime.”

There was the we at last, thought Korbelius. We are Henry the Eighth. We are not amused. “And I thought you loved the idea of beginning history all over again. What was the topic of your dissertation?”

Voss was momentarily taken aback by this non-sequitur.

“You’ve a doctorate, don’t you? I’m sure it’s Doctor Petra Voss. I can’t imagine you’d stop without one.”

Now she did get to her feet, looking lovelier than ever because of the blush lighting up her ivory cheeks. Korbelius would have liked to comment on this adorable blush, its delicate rose color, the piquant way it set off her eyes.

“That’s enough for today. Guards!”

3.

“Shh.” Birm got up from his chair, tiptoed down the hallway, cocked his head, tiptoed back.

Erko watched him sit down then went on musing. “Do we all dream about Petra Voss, or is it only me?”

“Sometimes I daydream about her,” Birm admitted.

“Sexy daydreams?”

“Not. . . exactly.”

“Then what?”

“Mostly scary, I guess. Well, once or twice a little sexy. But scary sexy. You know?”

“You’re still a bachelor. I’m almost ashamed to tell you what she gets up to in my dreams.” Erko lowered his voice. “There are feather dusters and horsewhips and lacy under things.” He looked into the cell. “And you, prisoner-poet? You a bachelor too?”

“A bachelor for a second time. Divorced.”

“And what about Voss? You must dream about her, right?”

“I do, yes. I dreamt about her last night.”

“Ah. Okay, out with it.”

Erko scraped his chair right up to the bars of the cell.

“Hey, keep it down,” Birm pleaded anxiously.

“The dream,” Erko demanded.

“I’ve always been impressed by people who can recollect their dreams, like Freud’s patients. Such detail, it’s admirable. Mine always start to evaporate the minute I wake up.”

“Come on. Don’t you remember anything?”

“Some. We were in a hotel room in the mountains. The place was a little like the sanitarium I stayed in with my mother when I was a boy, but this room was much grander, and the mountains were higher. It felt, well, Swiss.”

“No mama this time, though?” said Erko lasciviously.

“There were chairs and sofas, an old-fashioned bed with a canopy, and a huge fireplace. One whole wall was windows from top to bottom. You could see the mountains covered with spruce and pine. There was snow on the boughs and more was falling. Big silent flakes.”

“Sounds cozy,” Birm chimed in.

“Pretty snug,” Erko agreed. “So what happened?”

“She was dressed in her usual way—except her suit was jet black. Her hair was pulled back even more than usual, so severely it looked like it must hurt. All I had on was a pair of light pajamas. I remember feeling chilly.”

“The temperature dropped twenty degrees last night,” explained Birm.

“What about the bed?”

“Let’s see. We were sitting on easy chairs on either side of the bed. Her side was near the fireplace. I remember there was a good blaze going in it.”

“And?”

“She made a long speech about why I ought to move over to her side of the bed. I think there was a lot about politics and history and economics in it, but all I can recall her saying is ‘It’s warmer on this side.’”

“So,” said Erko, “did you ever make use of that soft Swiss bed with the—what was it?—the canopy?”

“As a matter of fact, I climbed into it. It felt like the inside of a mitten.”

“Ah ha. And Voss—she joined you?”

“She just kept on delivering her interminable tractate so I did what such things always make me do. I fell asleep.”

“Bullshit. People don’t fall asleep in their dreams.”

“I did. And woke up on this cot. My feet were blue.”

“A sad dream,” sighed Birm.

“What a tease,” griped Erko. “You made it all up, didn’t you?”

“No, it was a real dream. Well, maybe I embroidered a little. Deepest apologies. Anyway, a man can’t be held responsible for his dreams, only for the way he understands them and what he does with them.”

“How do you mean, does with them?” asked Birm.

“Well, say you dreamt of a treasure buried under a bridge in the town of Britow. Gold and lots of banknotes. You could wake up and go to Britow, find yourself a spade, climb down under the bridge, and start digging. Or you could shrug off the dream, blame it on the black sausage you had for dinner, take a leak, then make yourself a strong cup of coffee.”

“I’d run to Britow,” said Birm enthusiastically.

“That’s because you’re a superstitious moron,” groused Erko.

“And yet,” Korbelius reflected, “who’s to say which is more foolish—burying a dream or trying to dig it up?”

“You’re being a poet again. If you don’t mind, please go back to being a prisoner. If I had any eggs around here, I’d scramble poets just like them.”

Birm chuckled.

Korbelius lay back on his cot, put his hands behind his head, and mumbled a line of verse, one that never failed to comfort him in the way running his finger over the edge of his blanket had when he was little. The house was quiet and the world was calm.

4.

Voss had let down her hair. It was nearly black with auburn highlights, straight—save for a sine curve on the right side—and fell to the small of her back. Korbelius was like a mineralogist stumbling on a vein of silver where he’d expected only coal. He would have liked to touch the hair, study it, weigh it in his hands. Then he noticed that the topmost button of her blouse was undone.

Tack, apparently, was being changed again.

“Last time you asked about my doctoral dissertation. It was on T. S. Eliot. In particular, his plays.”

“Eliot? Really?”

“In fact, you remind me of Murder in the Cathedral? You know it?”

“Sure. It’s the only famous one. ‘Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?’”

“You remind me of Becket.”

“That’s surprising.”

“I wouldn’t have thought you’d be attracted to a man who described himself as a Royalist, an Anglo-Catholic.”

“And a classicist. So what? He was a good writer.”

“You say that as if it hardly matters what Eliot wrote.”

“It doesn’t. At least not any more. Because he’s dead. What you write matters only because you’re alive and a darling of the human rights industry. What you write certainly matters to my superiors, as they’re pleased to call themselves. To them, I assure you, your words matter. In fact, I’d say they’re your most attentive readers. And I count myself among them. Don’t all writers yearn for attentive readers, Korbelius? You ought to show some gratitude.”

Hair down, blouse a wee bit open, T. S. Eliot a topic of discussion, and now she was addressing him by his proper name—Korbelius braced himself.

“So,” he said, “Thomas Stearns Eliot and Thomas à Becket.”

“And Thomas Karl Korbelius.”

First and middle names as well, forsooth. Tack was indeed being altered. You want to get at to writer, send a knockout Cambridge Ph.D. in English Lit. Writers are susceptible to readers—good readers, at least. Korbelius, picturing himself leaning over her shoulder as she read his Nocturnes or The Bronze Lantern, did feel something akin to gratitude—up to a point, in his fashion.

“In Eliot’s play, as you may remember, Becket four tempters visit Becket.”

“Like Scrooge’s four ghosts.”

“I never made the connection, but I suppose it’s much the same psychological projection.”

“Bet you were always the first kid in the class to stick up a hand,” he wanted to say but kept his trap shut.

Voss rose and took the three steps that would have been necessary to reach the window, had there been one.

“The first temptation was to return to a life of levity, an unengaged life pas engagé, what Kierkegaard—that twisted Dane you like so much—called aesthetic existence.”

“Life as an agglomeration of one-night stands? Are you telling me that’s what’s on offer?”

She smiled. “It didn’t appeal to Becket and wouldn’t to you. Tempter Number Two says Becket should cast off his spiritual inhibitions, unify church and state, and so exalt his power.”

“Can you see me becoming the next so-called Minister of soi-disant Culture?”

Voss took a sudden step toward him. He would have drawn back but, as he was in the kiddie chair and couldn’t, he studied her left ear, protruding from the cascade of hair. Considered as an object, she’s perfect, he mused; but, as a subject, hazardous.

“Number three: make a marriage of convenience with the discontented barons and put yourself at the head of a putsch.”

“There aren’t any proper barons any more. It’s too bad. Just anxious functionaries taking their cuts and perfecting their nepotism. Revolutionaries who’d never rebel against anything.”

Voss returned to her seat, took a deep breath, then struck the desk with her fist. “These three Thomas expected. He was prepared, knew them of old. He was like the handsome Rabbi Ishmael being led out to his execution. A Roman matron offered to spare his life if he’d just raise his head so she could get a better look at him. ‘Shall I forfeit the bliss of eternal life for an hour of pleasures such as those!’ Again, you remind me of him.”

“I’m hardly handsome, but your erudition is stunning. I suppose the lady wasn’t exactly pleased/”

“ ‘Flay him,’ she commanded the soldiers, and they did.”

“Flayed him?”

“Every inch. So it’s written.”

Korbelius playfully composed a couplet for her on the spot: “A fate that leaves me undismayed. / What decent poet’s not half-flayed?”

“Bravo, Cyrano,” she said flatly.

“And the fourth temptation? Excuse me, I’ve forgotten.”

“That was the one Thomas didn’t expect but, I’m thinking, you do.”

“Yes?”

“To become a saint and martyr. To be immortal, to be venerated.” She drew a paperback from the desk drawer, opened it and began to read:

“But think, Thomas, think of glory after death.

When king is dead, there’s another king. . .

King is forgotten, when another shall come:

Saint and martyr rule from the tomb.”

“Sainthood’s not for me. I’m just a non-practicing vegetarian.”

“Yet you’ve got a yen for the permanent, just like Becket. You want what Eliot calls an ‘enduring crown.’”

“Oh, I don’t know about that. Frankly, I’ve never been able to make out if I’ve got too much ambition or not enough.”

She took up the book again.

“You have also thought, sometimes at your prayers,

Sometimes hesitating at the angles of the stairs. . .

That nothing lasts. . .

Men shall declare that there was no mystery

About this man who played a certain part in history.”

“‘Angle of the stairs’—that’s good. And I like the rhymes. Don’t you find that Eliot’s always come as a pleasant surprise?”

“As I said, you’re ready while Thomas was not. ‘Who are you, tempting me with my own desires?’ That’s what he asks. But not you, Korbelius, not you.”

“You have an awfully roundabout way of offering a man a job as a hack.”

“A hack?”

“The Writers’ Union’s chockfull of ‘em.”

“They perform useful work.”

“Yes, your heroes of culture are quite. . . useful.”

She shook this off. “When Thomas complains that he offers ‘dreams to damnation,’ the tempter replies, ‘You have often dreamt them.’ Becket won’t do the right thing for the wrong reason. But you, Korbelius—why not do the wrong thing for the right reason? It would make a change.”

“I haven’t dreamt any such dreams,” he replied, thinking back on the half-invented bedroom in the Alps.

“But you have. It’s all there in ‘Death of the Author.’”

“That’s not what the poem’s about.”

“Oh, really? Didn’t Socrates say no poet understands his own words? You may use words to obscure yourself, Korbelius, but they disclose what you want.” Here, Voss stood again and stalked around the desk until her knees were a ping-pong racquet’s distance from his chin. Looking down at him, she scoffingly recited:

“It was in Mars’s month, time of

ultimate frosts, contorted mud,

and day broke brisk; a steel wind

brightened by frozen sunlight

whipped the bedecked catafalque

into a clipper all unfurled.

Schoolchildren marched up the stairs

to look, each with a flower made

of orange, green, or yellow yarn.

It seemed to them the set face still

concentrated on a final story

trapped beneath the map-like brow.

The children wore their leather shoes,

old scuffs freshly concealed by

shiny polish; their small cold feet

clattered on the pine. They came,

both children and shoes, in pairs,

boy girl, girl boy, hand in hand.

The fat mayor spoke, then the thin priest.

Even ladies furred and muffed who

had slept with the author or claimed to

shivered in that storyless, poemless

atmosphere. A sister spoke of a

brother. A professor summed up.

Safely dead at last, safely dead,

the story of his story’s dénouement,

all complications unknotted, at rest

all energies, fate with character

equalized. He’s his last name now,

a body we can do with as we wish.”

Voss raised her eyebrows then her voice. “Well?”

He remained silent.

“Listen to me. People want to be secure, to be rich, not free. And if they’re rich and secure enough they think they are free, and so they are—free not to grovel, not to starve.” She lowered her face to his. “Join us, Korbelius. Help us.”

Korbelius looked into Voss’ stony dark eyes and was indeed tempted. The trick, he said to himself, is not to sell your soul to the Devil or to God.

And so, for the umpteenth time, he said, “No.”

5.

In later years, after everything had suddenly and unexpectedly changed, Korbelius visited Switzerland. He walked among the famous banks of Zürich, accepted a Helvetian award on the shore of Lake Geneva, ascended into the Alps in a funicular. One novella, three poems, and a short story were set there; but he never wrote down the Swiss tale that meant the most to him. It was his favorite among what he privately called his Camp Fantasies, most of which had plots built around menus.

They had given up on him and he was to be transferred. Birm and Erko had come secretly to say farewell, let in by the night shift. Erko gave him a plastic bag holding a sausage, a block of chocolate, and a flask of homemade slivovitz. Birm gave him only his tears.

“You’ll be remembered,” said Erko stiffly.

“Or forgotten,” Korbelius had replied.

Three winters he endured in the barracks, down in the labor pit, typing up Major Kulm’s vapid reports. Into the latter he could not resist interpolating a few colorful tropes of his own, such as “immovable as a socialist sedan” or “not enough meat to fill a weevil’s belly.” He got to know murderers, rapists, embezzlers, anarchists, fascists, and disgraced bureaucrats. He liked the murderers best.

The cold in the camp was forged of iron. Winter was a sentence within a sentence, beginning in October and letting up, reluctantly, in June. He imagined that the cold in Switzerland was of an entirely different order; there the frost was elective, salubrious—even warm. Suffering was so rare in that country it had to be imported. Even the wealthy were decent folk. It was a place apart. The Magic Mountain. Tender Is the Night. Castalia.

In his camp fantasy, Petra Voss undergoes an epiphany, melts, changes her mind. She weaves the sunlight in her let-down hair, turns toward him and away from the stuffed men, headpieces stuffed with straw. She becomes humbler, softer; she takes to heart what Eliot had to say, save for the Anglo-Catholicism and anti-Semitism.

The plot is embarrassingly unoriginal. Voss conspires with Erko and Birm to smuggle him across the frontier in a lumber truck and, at the last minute, declares she’ll be coming too. She says it’s because she misses Cambridge and sentimentally quotes Wordsworth: . . . turrets and pinnacles in answering files extended high above a dusky grove.

Korbelius’ dream of deliverance includes his accumulated royalties, shoals of European admirers, not-entirely-deranged groupies, grinning publishers. He’s a hot literary property who gives public readings at all the best universities and, when begged for a review, always praises his rivals to the skies. But it’s Petra Voss who becomes the focus of globalized curiosity. Photographs of her appear in Marie-Claire, The Economist, Der Spiegel, Elle, The National Review, Lip.

They are a couple; they are The Couple. A circle of friends forms around them, sympathetic people possessed of old country houses and an unlimited spectrum of opinions. One, an orthodontist, rectifies Korbelius’ neglected teeth. Another, a famous painter, executes a portrait of Petra which becomes famous itself. Many of their friends have small children who love joking and tumbling around with Korbelius, become bear-like on French and Italian cuisine, yet fall silent and stand stock still when confronted with the statuesque Petra.

The fantasy ends in the Swiss hotel room, the one with the canopy bed, outsized fireplace, and wall of windows. Petra sits on one side of the bed, her legs bare. She pretends to denounce him, playfully using her old, cold interrogator’s voice which he loves to hear. “You’re a counter-revolutionary running dog!”

He raises a finger. “Correction. I’m an a-political, non-practicing, moderately revolutionary counter-revolutionary lazy puppy.”

She yawns. “The fire makes the room so warm. Warm.” She sighs, stands, drops her peignoir, and lies face down on the mattress.

From his side of the bed Korbelius watches, scrutinizes.

He would like to work out the geometry of her body—the ineffable series of curves from heel to calf, calf to thigh, thigh to buttock, then the sublime dip into the small of the back, the gentle slope rounding briefly in the shoulders, the long neck and the head with its sheet of heavy dark hair. He gets up, hovers over her, not daring to breathe, inebriated by the scent rising from her nape, and commits her skin to memory.

Korbelius gently covers her with the soft Swiss duvet then tiptoes to the sturdy Swiss desk beside the wall of Swiss windows.

He sits and begins to write.

Robert Wexelblatt is a professor of humanities at Boston University’s College of General Studies. He has published eight collections of short stories; two books of essays; two short novels; two books of poems; stories, essays, and poems in a variety of journals, and a novel awarded the Indie Book Awards first prize for fiction.

Leave a Reply