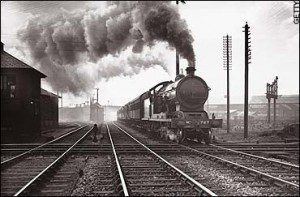

The train stopped, puffing out balls of dark, sulphur-scented smoke into the air. A woman dressed in black stepped down from one of the third-class carriages. Walking over to the restaurant, she bought a few cupfuls of coffee and poured them into a thermos while her half-dozen children gazed around at the passers-by.

The youngest but one, a slight little boy of six, with large black eyes and sunken cheeks, had been crying since morning, had a runny little nose and wanted his daddy. He hadn’t drunk his morning coffee, had refused to eat a slice of bread and had spurned the sweet his mother, surreptitiously avoiding the others’ eyes, had attempted to stuff into his mouth. His body heaved in sudden, shaky movements, which were accompanied by sobs. Streams of tears flowed down into the corner of his mouth. When an attempt was made to give his face a wash, he caused a hell of a fuss, working himself up into a state that was pitiful to behold.

His mother assured him his father wouldn’t be long, that he’d gone to buy a packet of those biscuits the boy liked so much. She sat him on her lap and rocked him from side to side, promising him a tricycle and a whole pile of presents. When the train set off again, she pointed out the coursing waters of the river, the buffaloes grazing on its banks, the sweet little children who waved up at the passengers and even a kite darting through the air above a flood meadow. Could he see the calves charging along with their tails in the air? And the women gathering the rice harvest? What about the car that had stopped on the road? Did her son want a car?

No, the little one wanted his daddy and wouldn’t relax. He sat motionless where she had set him, mouth agape, spittle dribbling down to stain his shirt, his helpless posture that of a little bird toppled over in its nest, its unfledged wings shivering in the cold.

His father had vanished at ten that morning, when the slightly warmer breeze blowing into the carriage had announced it was time for his first drink. At every station the other passengers had seen him take his life in his hands and jump down from the train before it halted to go slake his thirst at the bar. Between times he went from wagon to wagon, talking to strangers as if they were old friends and singing bawdy songs that made the young ladies blush and the adolescents roar with laughter. He snuggled down impudently between women. He rose again to his feet and strode proudly around the carriage, not deigning to be interrupted.

He had been in theatre, an actor. Did you all hear? He had been an actor in the theatre and had built up a great reputation on stage. The youngsters wouldn’t have seen him. Did they want to hear one of his most famous songs, which in the year such-and-such had been on everybody’s lips? And, with the rasping voice of a drunkard, he began to sing in a syncopated rhythm, swaying his now-scrawny body from side to side, marking time by bringing his thumb and his forefinger together in a circle. Didn’t they think it was a fine tune? The first edition of his record had made him ten thousand. The second a little less. The governor had written him a letter of congratulations. A handsome figure, the governor. Tall, bald, and very white. Yes, he had trodden the boards. There weren’t any actors left these days. But he had quit that life in favour of one that would give him a fat pay-out. 400 rupees. He liked to exercise his voice every now and then. He planned to release a few records. They’d made him some tempting offers. But he wanted more. What were 200 rupees in the current climate? Money drained away like water

“Hey, Uncle” – said a boy, hiding his smile with his hands – “it’s urraca your money drains away like”

The man pretended not to have understood the allusion and went to bother an old lady who was taking titbits to a son working in Bombay.

“So, Mother, you’re off to Bombay?” he asked “There you’ll see houses two hundred floors high and motorcars with twenty wheels. I’m not lying. Do you want me to help put your bundles up in the baggage rack? You’ll be more comfortable that way”.

The old lady, however, was afraid the tasty morsels would get stolen.

When the man finally returned to the carriage his family was travelling in, his wife tried to keep him by her side, asking him to take care of their son, who wouldn’t stop crying. In her arms she was carrying the other son, the youngest, only a few months old, juggling his nappies, milk bottle and a plastic bag as if she were a fourhanded goddess.

It was hard to pin down the woman’s age; sometimes she looked old, at others, judging by the suppleness of her strong, wide hips, just worn out in the prime of life. Her shabby clothing, meagre baggage and the lack of any gold jewellery betrayed her extreme indigence. The hard lines that shaped her face, not allowing her even to spare a smile for her children, were testament to an intense suffering become second nature.

“Look after the children?” he answered. No way, that wasn’t the man’s role. And he broke into a song about marriage. All the same he raised his son up into his arms and rocked him until he was asleep enough to place on the floor, down on the mat where the rest of the brood were noisily playing cards. When the train reached the next stop, he hurried off in search of another tipple.

“Don’t drink any more!” she pleaded in his ear, “At least, not today…”

“You think I’m going to drink?” He raised his voice: “No, I’m sorting out this business with Costa. He’s on the train. He says that as soon as we arrive he’ll pay me those 800 rupees, commission on top”.

The woman asked a girl to take care of her baby son for a moment whilst she went to the toilet to freshen up. She returned and sat down again, looking out of the corner of her eye at her fellow passengers, who had been both following the soap opera and, out of politeness, doing their best to ignore it.

Amongst their number was a man who reminded her of old times.

David… He had the same way of smoking. The same tousled hair. David, the man she had loved, the man who could perhaps have changed her fate. Was that the truth? Or would she have needed to change the course of his life? In any case, the results would have been far from unpleasant. He was a visionary. A poet who cast to the wind verses she couldn’t understand, and who scrawled down complicated tangles of words. He had once written that she was a droplet of luminescence piercing the oily pool of night. She hadn’t liked that, and had asked him to call her rosebud or pure flower of scented jasmine. David had retorted that there weren’t women like rosebuds or scented jasmine anymore. Not even her? Feigning tears, she had run towards the bedroom. He had dashed after her, saying that for every rule there was an exception. They had sat on the bed, not breathing a word. David stared into her eyes as if he wanted to hypnotise her. He started to speak of love, of her dizzying beauty, of the incomparable attractions of her eyes with such art that she grew giddy. He then whispered words that she wanted not to hear but which at the same time intoxicated her, awakening her irresistibly to love. Her surrender filled her with intuitions of bitter sweetness. She wanted David to take her in his arms and show her the secrets he was whispering in her ear. She tried to react, to run out of the room, to fight back.

Sometimes she wondered if their relationship was viable, her just the maid of a rich family and him a poet with great cachet amongst the intelligentsia. Her mother, who had noticed her preoccupation, advised her to choose a boy from their village, one who worked in the city and was honest and god-fearing, rather than allowing herself to be deceived by a man who had no respect for morality and placed no limits on his license. David didn’t love her. He didn’t love anybody. She thought over her mother’s arguments all the while allowing herself to become enslaved to love. She asked her mother if she wanted her fate hitched to a man like cousin Roque, who had been ravaged by drink, and ate and slept like an animal, or some servant who would never rise above kitchen level, and with whom she would end up coarsened and rough. Didn’t her mother know about her love story with the bhatkar ’s son? He loved her. She loved him back. God had cast some of his creatures from his head, some from his arms and others still from his lower limbs. From which level did her mother expect her to choose?

She had sought out Rosa, a cousin with revolutionary inclinations, to ask her opinion.

“Want to know how it seems to me? I am familiar with David. That is to say, I know his poetry. I support your point of view, but I can’t defend it in your particular case. I’m a pragmatist. Marriages like this end in disaster. It is, however, necessary they take place. Do you see the contradiction in my argument?”

One day David appeared dead. Neither the police nor the doctors could ascertain a cause of death. She cried like a lost soul. Some months later she accepted the proposal of the theatre actor, whose songs plunged her into a deep despondency.

The train pulled up at a station in the foothills of the looming mountain range.

“To hell with it!” said the woman’s husband to himself as he ran to a shack hidden in the trees nearby. “Tomorrow I shan’t be able to drink this fine wine. Behind these mountains reigns the dry law. Even that stinking brew of rust and excrement is banned, though we drink it regardless. This stuff is different. A delight lifting us to heaven. If they only knew how good feni and urraca taste… Wine is bad for your health, they say…But it does me a power of good… Huh! I feel my head spin when I don’t drink. In my village Dr Franco says wine is a tonic. And he knocks back enough. That’s because he’s in the know, eh? The people who live on the far bank of the river think it makes you more fertile. Honest truth. What else can a person do after working like a beast for ten hours, apart from get home dead tired and start snoring away? They’re right. It’s all part of their plan. But women can have kids all the same, and that ruins the plan they have. So drinking keeps your conscience clear. Because women are amazing creatures, and no one can stop them making a move. When they want to, and when they don’t too. Oh, look how full this place is!”

He went in and sat at a table made of dull, rusty tin.

“A large glass, a rupee measure” he asked the boy who came over to take his order.

He began to sip his wine slowly and methodically and looked round with the sly eyes of a mean drunk, observing the comings and goings in the tavern, the movements of the barman and the yawns of the landlord.

Another group of customers came in. There were no chairs free, so they formed a wall round the owner, sipping drinks amidst peals of laughter.

“Your feni is a stomach-ripper. Tobacco in the distillation or what?” one of them asked.

“Tobacco costs the earth these days. The palm juice from these parts is of good quality, and the people who distil it are honest folk. You, sirs, are used to undrinkable rotgut and there’s the difference. Hundreds of bottles of this stuff are transported over these hills daily.”

“A bottle for the journey” one of them asked.

“Hey, Pinto, a bottle of the good stuff for these gentleman. Did the man who was just in here pay his tab?”

The barman replied that he didn’t know, and that therefore the man mustn’t have paid. He rushed off after the theatre actor, who already had a good head start.

“Oi! You haven’t paid the rupee you owed.”

“I gave it to your boss.”

“No you didn’t. Hand the money over, otherwise it’s me that’ll have to pay.”

“But I’ve paid already.”

“He says you haven’t, and he’ll make me cover the shortfall. I earn so little as it is…” the barman said in a limp voice.

The man shoved him out of the way, and walked off at twice the pace.

“Thief!” hissed the barman through gritted teeth “I’ll make you pay for this. The worst thing is that I’ll lose a day’s wages.”

The other, just before reaching a bend in the low trees, turned back, pulled a face and felt much more at ease.

At that moment a rock split the air, striking him at the base of the skull. He threw up his hands, gasped an oath and collapsed onto the red stone path.

The train’s whistle sounded. The iron rods and gears began to move to the jerky shunts of the engine, waking the child who began to cry again for his father.

His mother raised the boy back up onto her lap. Clasping his head against her bosom she whispered that his father would soon return, and wouldn’t leave them again until they reached their destination. She lifted him to the window to see the landscape’s sudden transmutation into sombre mountain green.

The rails pierced a diorama of mountains, illuminated by the sun, which shone down from not far above the horizon. As the train ate up the miles, the vistas grew short and the heat faded. Wherever you looked, there was not the smallest clearing, not the faintest hint of life, just the pre-historic majesty of the land, violated by that sliver of civilization climbing on and on. Not a flower in sight. Even the red stones gleaming below had a sinister hue, in league with the dark trunks of the trees and the drab ribbons of water that ran beneath their boughs.

The woman managed to convince her son to drink a cup of coffee and nibble a little stale bread, without butter.

The child stared open-mouthed at the monkeys leaping from branch to branch and the crows snatching crumbs from midair.

The train dragged itself up the slope, making the iron gantry upon which the tracks ran groan. From the damp sidewalls water trickled. Lush vegetation pushed its way out through the cracks. The air hung heavy with peppery scents. A few hundreds metres later, water ran out over mossy stones, in silence, spilling over into the gulleys and forming torrents that then mysteriously disappeared. For a moment it seemed like the train would pitch over into the abyss. It stopped on the brink, and rested.

Below, as if in an aerial photograph, lay a valley immersed already in the shadows of the afternoon. Here and there specks of red – hilltop houses – broke the monotonous expanse of green. The tracks of the railway gleamed. On the far side the mountain ridge was faintly illuminated.

“Where are we?” asked the woman in black.

A student ventured a few words of explanation.

“Are we going down that way?”

He laughed and replied that now the only way was up and that they had already travelled along the gleaming rails below.

The train set off once more.

The sun had disappeared. The first shadows of night began to settle. In the distance, the contours of the land faded from view. The last traces of the earth’s heat began to dissipate.

Nostalgia for home, for its coconut trees and fields of paddy, for the temples that far behind them splashed colour over the heavily populated coast, overcame the passengers. They began to sing. At first in a low murmur; then with throats wet with urraca. After their meal, a mandó once again defied the dull clatter of the wheels.

But the son of the woman in black was crying, and wanted his father.

There is a trend in the dénouement of short stories for symbol to take over from action and plot in order to crystallise meaning. “On the Train” closes with a description that draws back from the individual story of the woman to describe the movement of the train and all the passangers as they climb upwards into the Western Ghat Mountains. Travelling towards a border that no longer separates Goa from the rest of the subcontinent, the close suggests a collective, now orphaned of an unworthy father, moving forward uncertainly into an unknown future.

Translating Indo-Portuguese literature into English is always problematic. After the transition in Goa from Portuguese rule to integration into India, the Portuguese language was disestablished, and swiftly withered as the language of literature and culture, and replaced de facto with English. To translate between the two languages in a Goan context is not so much to switch between cultures, as to move across the boundary between Goa’s past and its present. In a sense, converting Indo-Portuguese literature to English is to confirm the fear for the future, that of disparition and replacement. This aspect is regrettable but cannot be avoided. Without such post-colonial translations, stories like “On the Train” with its record of a certain sort of Goan experience at a specific time and place in India and Indian history would be lost, or at least obscured, for future generations.

Epitácio Pais (1926 – 2010) is an Indo-Portuguese writer from Goa, described by Vimala Devi and Manuel de Seabra as “a short story writer of great vigour, whose prose is terse and suggestive. He feels the world around him in all its poetry and tragedy”. The bulk of Pais’s writing was done the end of Portuguese colonial rule in 1961. Appearing in the surviving Portuguese-language newspapers or broadcast on the programme “Renascença” of the Goa station of All-India Radio, Pais’s narratives deal with the shifting social, political and economic situation in the Goa in the first years of Indian rule.

Paul Melo e Castro lectures in Portuguese and Comparative Literature at the University of Glasgow. He has a long-standing interest in the Portuguese-language literature of Goa and is an occasional translator. His translations of Goan literature have appeared in Indian Literature, Muse India and Govapuri, amongst others. His most recent book-length translation is Vimala Devi’s Monsoon, Seagull, 2019. This translation was supported by the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Leave a Reply