Choosing between right and wrong isn’t hard. I mean you might still choose badly, but if you do, you know it’s wrong. Like if you’re at the pool and a baby crawls to the edge and slips into the water because her mother’s busy gossiping and drinking daiquiris. The right thing’s obvious: you fish the baby out. You’re a heroine and the mother’s grateful—also she’s going to feel terribly guilty. She knows that gossiping and drinking daiquiris and ignoring your baby is wrong. Her guilt, once it kicks in, will outlast the gratitude; it ought to, at least in my opinion. Anyway, not to fish the baby out of the pool would be wrong and if you didn’t then you’d be feeling guilty too.

What’s hard is to choose between two right things and two wrong ones. This is called a dilemma, from the Greek for “two propositions,” neither of which is attractive.

Recently I fell into a dilemma. Fell into sounds dramatic but it really did feel like tumbling accidentally into a mess—not a baby slipping into the pool so much as an explorer stumbling into quicksand.

I’m twelve years old. My birthday was last month. I’m the kind of person who looks up the etymology of dilemma, as you know. I read too much, according to my mother, but not my father. This is one of the only things about which they disagree. They’re both social democrats and vegetarians; neither is a good cook so the food at home is disgusting. Spiritually, I’m a vegetarian too but I eat meat at every opportunity, which proves you can know right from wrong and still choose what’s wrong. My parents didn’t have any other children because my father says about the worst things you can do to the planet is make more Americans. We consume five times our share of the world’s resources. This leads me to think I was probably an accident they neglected to correct. My parents feel good whenever they renounce something—chocolate or taking airplanes. The logical conclusion of their horror of exploiting the planet is to be dead. Mother works part-time at a consignment shop. Recycling is good for the planet. My father is a professor of classics, which means he knows Latin and Greek, dead languages that aren’t dead to him.

When I was in third grade I had my intelligence tested. The tests were pretty stupid but apparently I scored highly, so I was put in a special program for “gifted” children. I don’t much care for that word. “Gifted” suggests somebody decided to tune up my brain—God, maybe—and that it isn’t me. It also implies that having a high IQ is an entirely good thing, something to be happy about, like getting the very thing you’d been wanting all year for your birthday. That’s how I felt last month when I got my wonderful Oxford Universal Dictionary—I even love that it’s a used copy because that means Muriel Van Heusen cherished the big blue tome as much as I do. There’s a little sticker decorated with curlicues on the inside that says Ex Libris Muriel Van Heusen. I wouldn’t be surprised if Father chose it because of the Ex Libris. I wonder about what happened to the rest of Muriel’s books; I’m sure she’d never have given them up willingly so I suppose she died. Being smart isn’t always as good as getting an O.U.D as a gift. You can’t put it aside, for one thing, and it can make you feel alone and weird sometimes. In twelve years I’ve been called weird a lot more than gifted.

Three years ago I invented Fred. I didn’t need an imaginary friend because of Sophie Agnelli, my best friend. Fred was my imaginary little brother and, being imaginary, he used up no resources at all. Perhaps that’s why my parents humored me. “How’s Fred this morning? Oversleeping again, is he?” Mother would ask when I came down for my glutinous Scottish oatmeal. “Well, what sort of mischief did Fred get up to today?” Father inquired when he got home from the University. Fred had a normal IQ and was always getting into the sort of trouble seven-year-old boys do. As his big sister, I tried to teach him right from wrong, watched over him, and ordered him around.

In February of that year we had a snow day. Fred stayed out late playing with his friends, a bunch of ruffians. When it got dark I went to the back door and called him in for dinner. He ignored me and the hooligans yelled “weird Mother Julie” and laughed. I kept calling him: “Fred Podest, you come in right away!” Then Fred made an imaginary snowball—iceball, actually. “Throw it! Throw it!” hollered the thugs and Fred did. The back door was open just wide enough. Athletically speaking, it was quite a throw, especially for a seven-year-old. It covered fifteen yards and smashed square into my face. The delinquents gave a great high-pitched cheer. It really hurt. But when I complained to my parents and demanded condign punishment, they defended him. Mother said I was too bossy with Fred and maybe I had it coming. Father declared it a Herculean toss, imaginary or not. I had to admit they both made good points. It was like I’d struck myself with that imaginary iceball; I felt as if my parents preferred the non-existent, non-consuming, non-weird Fred to me. Is being real really an the advantage? Anyway, I got so mad I decided there and then to liquidate Fred. It was easy. I simply stopped thinking about him.

The next day my father asked “Where’s Fred?”

I made a face designed to express sincere puzzlement and raised my palms. “Who’s Fred?”

One of my first conversations with Saul Bendiner went like this, more or less:

-Just begin anywhere.

-Anywhere?

-Sure. Whatever comes to mind.

-Comes to mind?

– We have to begin somewhere or we’ll be stuck just staring at each other.

-What? Start with anything?

-Yep. Beginning, middle, end. Fire away.

-Are you getting annoyed with me?

– It’s just that you keep asking questions.

-You find that, what? Evasive?

-I am getting a tiniest bit exasperated.

-Well, what do you want me to talk about?

– Begin with school if you like. Or home. Or what you’re reading at the moment.

-Should I talk about what I’m reading now or a book I really love?

-Stop it, Julie.

-Stop what?

-Asking questions.

-Is that what I’ve been doing?

Dr. Saul Bendiner, 46, is a clinical research professor of psychology and a colleague of my father’s. Apparently they hit it off when, after a committee meeting, they got to talking about Freud’s fascination with Greek mythology. Psychology and Classics. But I suspect Dr. Bendiner’s warmth toward Professor Podest might have had an ulterior motive. He’d been awarded a grant to do research on “gifted” children. His graduate students infested my school, carrying tablets around with them to record our answers to age-appropriate leading questions. Are you having trouble making friends? Do you feel you’re being challenged? Do you like your teachers? If you have brothers and sisters at home, do your parents treat you differently from them? I think Dr. Bendiner knew the name Podest before he met my father because he knew about me. Maybe he even made a point of seeking out my father and seducing him with some blather about Cronus eating his children and Freud’s Band of Brothers story. He needed my father’s permission to study me and got it. My cooperation was essential too, of course. Father made me an eloquent speech about my duty to Contribute to Science. He said that Dr. Bendiner was a fine man, highly regarded in his field. Accidentally on purpose, he let slip that I had the highest IQ in the school and that was why the psychologist wanted to get to know me in particular. I agreed to go along but did so guardedly, cautiously, reluctantly, and resentfully. I didn’t exactly love the idea of being studied just because I’d answered some silly questions correctly.

I like behaving toward Dr. Bendiner as if he’s my shrink because this annoys him. He once called it resistance and I suppose he’s right. He’s really not so bad, Dr. Bendiner; it’s just fun to tease him.

Father committed the capital error of mentioning Fred to Dr. Bendiner. This empowered him to tease me back.

-So, Julie, How’d it go this week? Any imaginary siblings show up?

-Why is it everybody begins whatever they’re going to say with So? So, Julie, for instance. I mean, it’s I everywhere, even on public radio, to which my parents are addicted, by the way. Diplomats do it. Novelists and astronomers. Even the people interviewing them. So, how did you feel when they called you about the Nobel? So, when I was a kid I was into mugging old ladies. So, you’re saying Pluto means isn’t a planet after all?

-It’s just a convention. A transition.

-You mean like the high school kids saying like like every third word?

-I guess it’s like for grownups.

-And all the more maddening because they’re grownups. My English teacher wouldn’t stand for it.

-The little errors other people make—these bother you in big ways, don’t they?

-Well, so, like, you know. . . .

-Last week it was and I go, wasn’t it?

-God. And I go like what’s that all about and he goes like you don’t know and I’m all if that’s the way you feel.

-Sorry. I forgot about I’m all.

-I’m all is that what you really think and she’s all I don’t know what I think.

-So then, no little brothers this week? Not even one?

-Do you think I’m a language snob or whatever it is my English teacher is?

-No, not really.

-So I’m a throwback?

-So maybe I’m a throwback?

-I used the word correctly, as a synonym for thus or therefore, both of which sound stilted. Stilted is kind of a stilted word itself, isn’t it?

-Nonsense on stilts. Jeremy Bentham said that.

-Nonsense on stilts? I like it. What did he say was nonsense on stilts?

-The doctrine of natural rights.

-I’ve heard of them.

-Somehow I’m not surprised.

Notice that I mentioned my English teacher on purpose, twice, just to see if Dr. Bendiner would pick up on it but he didn’t. Something happened between me and Miss Gormley in September that had a big effect on me, on my feelings about right and wrong and justice, about the justice system. Eventually, I did tell Dr. Bendiner about what happened. He thought it was hilarious, but I think it’s left the sort of scar that lasts.

I’d already heard about Miss Gormley and saw her a couple of times in the hallway. “Look. Miss Gormley,” Luciana Choi whispered with a kind of awe and pointed furtively. The kids in her class talked about her obsessively. They were so scared of her they didn’t even make fun of her, as afraid she’d find out. Respect may not be next door to fear, but it certainly lives in the same neighborhood. Everybody agreed that she was “an amazing teacher,” but they said it in a way that made you suspect that what she mostly taught was Miss Gormley.

My English teacher is imperious. She speaks with an enunciation as buttoned-up as her tailored suits. Her eyes are the kind writers describe as penetrating. Her hairdo resembles the kind you see in sixty-year-old photographs of career women.

Miss Gormley insists on the “Miss,” as if it were a noble title, like Countess or Lady. “Ms.,” she observed contemptuously the first time some unfortunate called her Ms. Gormley, “is a slovenly neologism that mixes up Miss with Misses and furnishes no useful information. The purpose of language should be to reveal, not conceal.” Miss Gormley is given to sententious statements like this. She posts a new proverb on the walls every week, the latest being “Procrastination is the thief of time.” I like thinking of procrastination as a debonair cat burglar, sneaking into the house at night, swiping all the clocks.

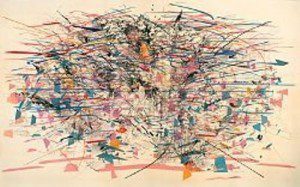

Unlike my classmates, I was happy to be assigned to Miss Gormley’s English class. On the first day she told us about her father, an imposing figure she mentions even more frequently than the comma splice. Like mine, he was a scholar of Greek and Latin. I rejoiced, thinking of this as a potential bond between us. One day she told us that her father made her read The Congressional Record aloud each morning over breakfast (oatmeal?). Maybe Miss Gormley’s father was a patriot because he also made her translate five of The Federalist Papers into Latin. “My father was a polymath,” she declared defiantly, assuming we knew what she meant and might doubt it. Polymath sounded like a particularly virulent strain of algebra to me and I had to look it up. I imagine Miss Gormley thinks of herself as a polymath, though less poly than her matchless father. In addition to going over the assigned readings, on Tuesdays she shows us slides of Great Art and on Fridays makes us listen to Great Music. “Education,” she proclaimed (pronounced Ed-u-ca-tion, never Edjucashun) “is about being something, not just having something.”

Our first paper assignment in Miss Gormley’s class was a five-paragraph essay about an interesting person. I had three candidates. There was my Aunt Beatrice who lives in Bel Air which is part of Los Angeles (Belairia, the opposite of Malaria?) with her third husband. She told me you can marry more money in a minute than you can make in a lifetime and let me try one of her cigarettes when I was five yeas old. Then there was, of course, Dr. Bendiner whom I’ve been studying as assiduously as he’s been studying me. Finally, there was, of course, Father. After careful consideration, first impressions being so decisive, I decided Miss Gormley would be impressed if I wrote about my father, so like her own, and then we’d form that bond.

The Monday after we turned in our essays, Miss Gormley walked among us, handing the papers back, each accompanied by a single public adjective: Acceptable. . . Substandard. . . Adequate. . . Depressing. . . Tolerable. . . Intolerable. . .Unintelligible. . . . She didn’t hand me either my essay or a demoralizing modifier. She returned to her desk at the front of the room. “Julie Podest,” she said with more than her customary portentousness, “I shall see you after school.” Shall. That was Miss Gormley all over. I had no appetite for the beets, mushroom, and quinoa salad Mother made for my lunch. To my classmates I was now an object of interest but it wasn’t the kind of attention you want. But maybe, I thought, this wasn’t a bad thing at all. Miss Gormley might have been so impressed with the scope of my vocabulary, the elegance of my sentences, and the congruence between our fathers that she wanted to have a personal chat with me, as equals, so to speak. There might even be tea. A compliment from the iron-clad Miss Gormley would be just shy of a Pulitzer Prize. On the other hand, I couldn’t help being anxious that she found my essay so bad that a single adjective—Moronic? Ungrammatical?—couldn’t sum up her loathing.

It was with this ambivalent trepidation that I approached Miss Gormley’s classroom at 3:30 sharp. Turned out I had it all wrong—or maybe right, although in the wrong way.

She was at her desk. “Please take a seat,” she said, standing up as she said it. Not a tall woman, Miss Gormley was seizing the high ground; she meant to talk down to me. I spied no teapot.

She held my essay up in front of me as if I might not recognize it. “This is exceptionally well written and unusually mature” (pronounced ma-ture, not machure). I felt relieved but shouldn’t have.

“I do not believe this is your work, Miss Podest. Did you copy it did you induce someone to write it for you?”

It was a binary diagnosis, no third alternative. I was speechless. Not my work? Because it was too good? I’d written four drafts? The injustice of the charge, the nature of the evidence for it, and the certainty with which it was delivered bowled me over as nothing in my life had before. What did the woman expect? Wasn’t this a program for the “gifted”? Worse yet was the chilling suspicion that she thought I’d turned in an essay on a vegetarian classics professor to worm my way into her father-adoring graces. “I did write it,” I wanted to scream, “and my father is a classics professor!” (Is not! Is too!) But all that came out—almost tearfully, I’m ashamed to admit—was the simple sentence: “You’re wrong.”

I don’t suppose it was these two words that gave pause to the dauntless Miss Gormley so much as my tone, which, watery eyes notwithstanding, was firm. I doubt anyone had said “You’re wrong” to her since her father corrected her Latin datives. But she quickly resumed her righteous air. She had determined a priori that no eleven-year-old, even if she was nearly twelve, could possibly have written what she’d read. Without further ado, she pronounced sentence.

“You will receive a failing grade for this paper, Julie, and I need hardly tell you what a memorandum of plagiarism will mean when I place it in your permanent record. You may leave now.”

For two days I suffered. In class, Miss Gormley didn’t call on me and I wouldn’t look at her. On the second day, my mother noticed I’d stopped eating and was making fists all the time. “What is it, Julie” she asked. “I know something’s wrong.” Mother had read a lot about “gifted” children. “Are you being bullied at school?”

Well, I was, in a way.

“Nothing’s wrong,” I mumbled. But Father got it out of me the next day. He did it not by asking, but just sitting down next to me on the couch and saying, “Whatever it is I’ll fix it.”

And he did. He went to school the next day, straight to the principal. Miss Gormley was as apologetic as somebody convinced of her infallibility could be. But I’d learned something, as I said, about justice—and its “system”. To be unjustly accused changes your view of the world, at least if you’re a month from your twelfth birthday. Everything looks darker when you know you can become an outcast at any moment. It makes you wonder if the people you’ve been told are guilty really are. You know grownups can be mistaken, and arrogant about it. Life’s not fair when good work can be punished. Non aequus, complained the Roman puer. Ce n’est pas juste, whines the petite demoiselle. Es gehr nicht nur, protests the kleines Kind. Fairness is every child’s first and purest notion of morality, and it was a joke. Authority should never be trusted. Justice is precious because, like diamonds, it’s rare.

I meet with Dr. Bendiner on Thursday afternoons in his University office. It’s twice the size of my father’s and twice as bright, too. His furniture looks like it was made by happy Danes, my father’s by miserable ex-East Germans.

Dr. Bendiner started out by giving me several tests or posing riddles designed to find out things about me without actually asking. Psychologists like fooling their subjects, especially, according to Psychology Today, students at Midwestern universities. The subjects don’t know they’re subjects. They think they’re giving electric shocks when they aren’t. They’re told they’ve been specially selected to take a course called Life Cycle of the Nematodes when they’re actually being but compared to another group that was told it was a required course, which also wasn’t true. Dr. Bendiner’s were duplicitous too, though not in the same way. For instance, he told me he wanted to test my “sequential cognition” when he gave me three seconds to answer this silly question:

Arkansas is south of Michigan but east of Texas which is

southeast of Oregon. Is Arkansas east or west of Oregon?

Nothing to do with sequential cognition, whatever that is, everything to do with geography.

Here’s another:

-If your house is on fire and you can only save one thing, what would it be?

-Me, of course.

-But you’re not a thing.

-To a fire I am.

On the third Thursday I suggested I ask him some questions.

-It would make a change. And you can tell as much from the questions I ask as from the answers I give, can’t you?

-You may be right. Okay. I’m sure you’ve got one in there. (He pointed to my backpack.)

-(I took out the sheets of notepaper I’d written on during study hall). I’ve got three.

-Oh.

-First one is a math question. That okay?

-(Hands up) All I can do is try.

-Okay. What’s the pattern in the following four sets of numbers. (I handed him the notepaper)

17 11 5 89 73 3 431 109 19 167 47 12

-(Long pause) Oh! They’re all prime numbers. (Looking pleased with himself)

-Good guess.

-(Frowning, perplexed) Not prime numbers?

-Almost all of them. Twelve isn’t a prime number.

-Then. . . ?

-Easy. Each set of numbers goes from bigger to smaller.

-But that’s so simple.

-I tricked you. Because I said it was a math problem and that there was a pattern you expected it was complicated and didn’t see how simple it is. (I’d picked up something from Psychology Today)

-Ever think of becoming a psychologist?

-Never.

-Okay, you’ve got another?

-Sure. This one’s a logic problem. Short.

-Logic. Shoot.

-A man claims to know the precise date and time of his death. How’s that possible?

-(Long pause, followed immediately by another long pause) I give up.

-(Clapping my hands) Because the judge told him. (Irrepressible laughter)

-(With a droll grin) Gallows’ humor.

-Good one, Dr. Bendiner.

-Thanks. I see you’ve got one more.

-Literary this time. You’ve read Hamlet?

-That would be the one about the Prince of Denmark?

-Yes, that Hamlet.

-Yes, as it happens I have read it.

-Then tell me why, if the dead king’s Hamlet’s father, Hamlet isn’t king.

-Hm. You know, I never thought of that. Why isn’t Hamlet king?

-Because Denmark’s kings were elected by the nobles. Polonius rigged the election for Claudius.

-No kidding? That explains a lot.

-(Nodding sagely) Uh-hum.

Miss Gormley assigned us Hamlet. The other English class got Julius Caesar which is shorter and easier but not so much about fathers. Maybe, like Sarah Bernhardt, Miss Gormley would like to see herself as Prince Hamlet, her upright and joyless father’s faithful child. Anyway, credit where it’s due; I plagiarized the question about why Hamlet isn’t king from Miss Gormley. It seemed fair enough.

Sophie Agnelli and I became best friends in first grade. This was two years before I was moved to the program for the “gifted,” an event which might have done our relationship in but didn’t.

Sophie has a port wine stain on her left cheek. In first grade, the other kids shied away from her; some made nasty remarks. Sophie says she’ll never forget how I just walked up to her in the playground and asked how she got such a pretty left cheek and could I touch it. As for me, it was enough that Sophie never once called me weird or went along with those who did. You could say we clung to each other ever since, a dyad—perfect for jacks, jump rope, and confidences. For two years we were the third and fourth worst players on the same hapless soccer team.

Sophie’s cousin Anna got married last month and she was ordered to be the flower girl, to strew rose petals on which Anna would walk into wedlock.

“There’s nobody younger,” she complained, “except for Tony but he’s six months old.”

Sophie wasn’t happy about the job and hated the lacy white dress she had to wear. But the pressure was enormous, like the Agnelli family. She gave in on the condition that I be invited to the wedding at Saint Catherine’s and to the reception at the bride’s parents’ house.

“It’s a huge old Victorian mansion, like an enormous doll house.”

Sophie is the best person I know. I especially like watching her with little kids. She’s a born mother as well as a great friend and maybe the two are connected. More than once I’ve had the feeling that she was mothering me.

Sophie was anxious about being a flower girl, about everybody looking at her, about tripping, about being too old to be a flower girl, about being teased.

“I need moral support,” she pleaded.

You don’t turn down your best friend so I said, “What do I have to wear?”

Saint Catherine’s was stuffed with flowers and dressed-up people. It had a wonderful aroma of old books, lingering incense, and decaying velvet. There was a lot to take in, too: stained glass windows, the Stations of the Cross, effigies of elongated saint, and the table in front of the Virgin Mary with votive candles burning all over it. Unlike Sophie, I had no tradition either to embrace or toss away. When I asked Mother about her religious views, she said “Oh, I guess I’m an agnostic.” She and was suffering from a cold that day and perhaps that’s why she sounded so vague; but then I don’t suppose agnostics ever sound quite definitive. Father told me he was raised a strict Lutheran but now was a strict atheist. Looking around Saint Catherine’s I thought this is real religion, by which I meant Catholicism gives you a lot to swallow and costs you something.

I got a new blue dress and it was all right. My mother picked it out. I felt lucky that I didn’t have to wear new shoes. Sophie’s outfit was as silly as she said it was. She scattered her rose petals like a pro, though she never looked up from the floor in front of her, not even to toss me a smile.

The bride’s Victorian house was a vast nineteenth-century wonder. There was a live band in the big living room which had been cleared for dancing. All kinds of food were laid out on a twenty-foot buffet table in the next room and there were chairs all over the first floor. Relieved after weeks of worry, Sophie volunteered to look after Tony while his parents danced, all the while chattering away to me about school and her cousin-the-bride. She also ranked the groomsmen on a ten-point scale. These had worn gray tailcoats, vests and funny white ties in church but now were stripped down for action. She scored an overweight, overenthusiastic dancer an eight, which I said was pretty generous. “Well,” she giggled, “he is the best man.”

The groom himself asked Sophie for a dance and one of his college pals asked me (Sophie gave him a six; I’d have said nine). After that, my best friend became a little giddy. So did I.

As we watched people throwing themselves around to “I’m a Real Wild Child,” Sophie whispered in my ear, “I know. Let’s play a game, you know, like we used to.” She nodded toward the Victorian’s long staircase which rose to a landing, turned, then continued into more elevated reaches, maybe a turret. With a wicked grin Sophie said, “Podest.”

On a rainy day when we were little I’d been invited to Sophie’s house for the afternoon and devised a turn-taking game inspired by my surname. Podest means landing in German. We’d only played it that once. The rules were to march up to the top of the stairs—to the landing—then jump down skipping first one step, then two, then three, and so on. It was the sort of pastime that might have gone on until one of us broke her neck. As it turned out, I sprained an ankle. There was a phone call to my mother, a fast and harrowingly silent drive to the emergency room, an ensuing x-ray and a pair of lengthy sermons.

Caught up in the gaiety of the occasion, I said, “Why not?”

We tiptoed up the stairs.

“Not sure how it’ll go in these dresses,” I said.

“Just try not to sprain your hem,” quipped Sophie.

When got to the landing we froze. There were loud voices coming from behind a bedroom door. The voices were loud. We could hear them clearly.

I held my finger up to my lips.

“That’s Aunt Gina.”

“Shh.”

“We shouldn’t—”

“Shh!”

-Nothing illegal about it. How many times do we have to tell you? Jesus.

-It is illegal and even if by some technicality it isn’t, it’s still unethical.

-Oh Christ. Tell him again and while you’re at it tell him to grow up.

-He’s not wrong. I mean what’s legal isn’t always ethical. And vice versa.”

“Uncle Frank,” Sophie whispered and began to tug at my arm.

“And the other?”

“His brother, I think. Victor. Come on, Julie. Let’s get out of here.”

-It’s up the buyer’s job to discover things. All we have to do is tell them a problem we know about.

-We do know about it.

-Not officially, we don’t. They don’t know we know. You keep quiet and we’re on solid ground.

-Look, Vic, it’s our one big chance.

-Hell’s bells. It’s survival.

-I’m disgusted. You two really disappoint me.

– Frank told me your mother dressed you like a girl. I can see why.

-Enough. Look, we’re not going to tell them and that’s it. You got it? It’s settled. Don’t forget, you get half—you want maybe half of half? a third of half?

Sophie’s eyes were big. She yanked on my arm. “Come on,” she hissed.

“What’s going on?”

Sophie said something nasty, let go of my arm, and tiptoed back downstairs to the music and wine, back to the Triumph of Life.

The next day I got a few facts out of her though, enough to figure out the rest. Her aunt’s husband and his brother—Frank and Vic—inherited a New York apartment building from their father and put it on the market. Worth millions, probably. But obviously, there was something the matter with the place—structural weakness, fire damage, bum wiring, roof trouble—something serious yet not easily spotted, even by a professional inspector. I couldn’t stop thinking about it and I didn’t try to.

I went online to do a little legal research.

When selling real estate, you are obligated to disclose problems that

could affect your property’s value or desirability. In most states, it is illegal

to fraudulently conceal major physical defects in your property. And many

states now require sellers to take proactive steps and provide written

disclosures about the condition of the property. However, in general,

you are responsible for disclosing only information within your personal

knowledge. In other words, you are not required to hire inspectors to

turn up problems you never had an inkling existed.

So Frank was right; but Vic was a lot more right.

I felt I had to report to Sophie. We told each other everything. It wasn’t the sort of thing you’d text about so I phoned her. She got angry.

“Why do you have to—I mean, it’s none of your business.”

“But we have to do something. Don’t you see?”

“No. I don’t.”

I suppose she felt like a passenger stuck in the middle of a canoe headed for a waterfall; she could see the looming disaster but she didn’t have the paddle. There was only one thing to do: get the person with the paddle to stop.

“You’re going to get everybody in trouble. Aunt Gina and Uncle Frank, my whole family.”

“What about the people they’re going to cheat?”

“I don’t know them and neither do you.”

Sophie raised her voice but spoke more slowly. “Listen to me, Julie. You do anything about this, you tell anybody at all, and I’m never going to speak to you again. You got that?”

My dilemma: I stick my nose into Agnelli family crookedness and lose my oldest, best—my only—friend. Or I keep mum and somebody gets defrauded then I feel guilty and sooner or later I resent Sophie for making me feel that way.

I had an urge to talk it over with my father (Whatever it is, I’ll fix it) but I hesitated. Either he’d do something and Sophie would hate me or, worse, he’d also tell me it was none of my business and then quote Homer or Aristotle or somebody.

Miss Gormley? The ed-u-ca-tor who accuses people without any evidence? Out of the question.

There was only one person I could talk to, by which I mean somebody who might possibly keep it confidential.

-Well, Julie, how’d that wedding go? Notice I said well, not so.

-Duly noted. The wedding was rather grand.

-Think you’ll do it someday?

-What?

-Get married.

I was in no mood to tease, let alone to be teased.

-You’ll never get me up in one of those things.

-Huh?

-It’s the caption to one of the great cartoons of all time. A pair of caterpillars crawling along a leaf and one of them looks up at a butterfly flying over them. Get it?

-The capacity to understand jokes indicates high intellectual development. That means you can’t be smart and miss irony. Can we talk about something else?

-Sure.

-I overheard something. At the wedding. The reception, actually.

-You were eavesdropping?

-Not on purpose.

-What did you hear?

-I heard my friend Sophie’s aunt and uncle his brother planning to do something wrong—illegal, I think.

I explained about the building in New York with the bad walls, leaky roof, or frayed wires.

-Sophie says it’s none of my business and not to mess with her family. She says if I open my big trap she’ll never speak to me again. She meant it, too.

Dr. Bendiner took off his glasses and rubbed his nose, something he does when he wants to think. He did the same thing the time I asked him about Hamlet.

-Maybe you heard wrong. And maybe it really isn’t any of your business.

I took a deep breath.

-Remember, I’m in my formative years and you’re an authority figure. Are you saying not to care about whether something’s right and wrong unless it affects me?

-Well, this does affect you. It affects your friendship with Sophie.

I shrugged.

-That’s all you’ve got?

-What would you do, if you wanted to do something?

-I’d find out who the buyer is and warn them, of course. You can probably find stuff like that out on the Internet. Look, I just can’t stand injustice. Remember that Miss Gormley story I told you? The plagiarism I didn’t commit?”

“All vices are social, all virtues personal. The simplest test for the morality of an act is the willingness to make it public.”

“You’re just quoting. That’s evasive. I want to know what you think, Dr. Bendiner. Just you.”

He rubbed his nose again. “What I think is that you’ll make up your own mind whatever I say. I also think whatever you decide will be right. Probably. I trust you.”

“What? That’s it?”

He gave a little shrug. “More or less.”

“Then I’m on my own?”

“We all are, Julie.”

“The gifted, you mean?”

Dr. Bendiner put his glasses back on; perhaps there was nothing more for him to think about. “You’ll let me know how you work it out, won’t you?” I could almost see the article taking shape behind his lenses.

…………………………………x…………………………………………….x……………………………………………..

Robert Wexelblatt is a professor of humanities at Boston University’s College of General Studies. He has published eight collections of short stories; two books of essays; two short novels; two books of poems; stories, essays, and poems in a variety of journals, and a novel awarded the Indie Book Awards first prize for fiction.

Leave a Reply