This story is part of Amaravati Kathalu, an anthology of Telugu stories set in the rural milieu of Amaravati, a village on the banks of the Krishna River in Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh. The stories reflect the life and times of Amaravati in the 1940s and ’50s, capturing the ethnic culture, traditions, habits, and social norms of the local people.

To retain the native flavor, certain food items, local flora, and everyday objects have been referred to by their original Telugu names, with English equivalents provided in brackets. Some liberties were also taken by deviating slightly from the original text to preserve the essence and mood of the story, prioritizing the spirit of the narrative over a literal translation.

A day ends, another begins. As we reflect on the day that has passed, we know that the new one will inevitably pass as well.

On one such passing day, Pichayya garu passed away. In this world, many people pass away, and Pichayya garu’s passing was not extraordinary. He was not a poet, nor a singer, nor anything of that sort. If we consider what he accomplished in life, there’s nothing remarkable to speak of. Like a small fish swimming underwater, oblivious to the river’s rushing current, and like a still wavelet on a placid lake, he lived out his life, merging imperceptibly with the flow of life. He was more than just quiet; he lived as if he were silence itself, entirely integrated into a state of quietude. To understand a life like his, it is enough to observe just one typical day.

Each morning, as soon as Pichayya garu arrived on the stone platform in front of his house, his wife Seetamma would have his Kumbhakonam Chembu (a small, bronze water jug) ready for him, along with Kachika (cow dung ash used as toothpowder) and a Tataku (a tongue cleaner made from a palm leaf). After washing his face, Pichayya garu would go directly to the Krishna River. With a thin towel wrapped around his waist, he made it a habit to take his customary dip, regardless of the weather. Standing chest-deep in the water, he would perform his Sandhya Vandanam (Daily Salutations), fill his chembu with the holy water, and set off towards the temple. On his way, he would sprinkle the cool river water on the children playing outside their homes. As they exclaimed, “Cold! Cold!”, he would continue on his way with a gentle smile. He would pause by the Ganneru (oleander) tree near the temple’s second prakaram (boundary wall) to pluck a few blossoms, murmuring to himself, “Where have the two buds gone that were here yesterday?” He knew each branch, twig, flower, and bud as intimately as a friend. Tucking a few punnaga (tuberose) flowers into his chembu, he would move towards the maredu (bael) trees. After gathering a handful of tender leaves, he would climb the steps leading to the third prakaram.

By the time Pichayya garu arrived, the temple priests would already be ready, having completed the abhishekam (ceremonial anointing) for the Deity, Amareswara. Pichayya garu would then perform his own abhishekam to Amareswara with the Krishna water he had brought along and offer puja (worship) with the leaves and flowers. No one knew which puja it was, for his lips never moved, and his chanting was never audible. Only the silent Deity might have known his silent prayer. Afterwards, he would descend, ring the temple bell, take leave of the Deity, circumambulate the Nandi, have darshan of Bala Chamundeswari, and prostrate before Her. He would then apply the saffron powder taken from the Mother’s feet to his forehead and come into the mandapam (pillared courtyard) to sit for a while.

By that time, the Brahmins who had performed the abhishekam would have gathered there, engrossed in all sorts of discussions—rising prices, the Avakaya pickle, Pakistan, or the latest gossip about someone who had eloped. Pichayya garu would listen quietly to everything. Occasionally, if Lingayya asked, “Pichayya garu, do you agree?” he would simply respond with a silent smile, never opening his mouth to speak. Now and then, he would glance up and count the sparrows that fluttered down to the Gali Gopuram (temple tower).

While he maintained such silence in observing the world around him, everything would change as soon as he stepped into his home. He would shout at the top of his voice, “What’s the chutney for today?” When Seetamma garu responded with, “Chutney (condiment) of cucumber pieces” or “Chutney made of tender tamarind leaves,” he would routinely caution, “Make sure it has enough karam (spicy with red or green chillies).” Pichayya garu insisted on freshly ground chutney every day, with a generous proportion of karam. Otherwise, he would fuss a great deal.

After his meal, with betel nut powder in his mouth, Pichayya garu would recline on his nulaka mancham (a cot with a coarse fiber netting). Seetamma garu would then join him to apply castor oil on his feet. As he dozed off, still chewing the nut powder, Seetamma garu too would lay flat beside him, resting her head on the foot-rest near his feet.

In the evenings, Pichayya garu would take a stroll around the neighborhood. His daily tête-à-tête with the priest at the Panduranga Swamy temple would typically go something like this:

“Which curry today?”

“Snake guard.”

“And chutney?”

“Kothimeera Karam.(Spicy Coriander paste)”

“How many pujas today?”

“Two.”

“Was it fetching?”

“Somewhat…” laughs the priest.

Pichayya garu too would laugh.

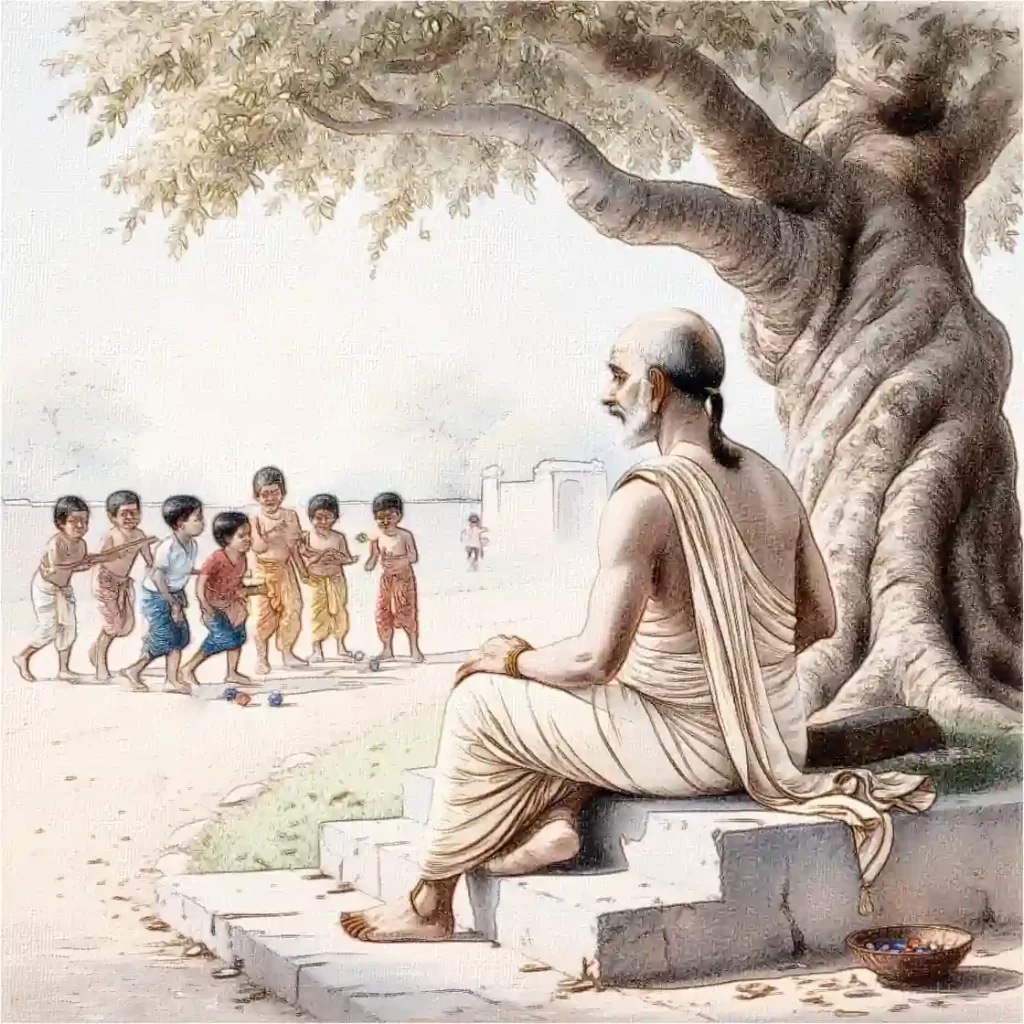

From there, he would go and sit for a while on the steps of the Rama temple in the main bazaar, watching the children play marbles. Along with the children, he too would count the marbles. During the season, he would buy a measure of Regi-jujube nuts and distribute them—one nut each—to the children.

By twilight, he would return to the temple. Inside, his usual spot was like a reserved seat for him. He would sit there quietly, watching the parrots perched on the temple tower or the gentle swaying of the Jammi tree. When the temple doors closed, he would collect the Vadapappu prasadam (green gram soaked in water) in the corner of his upper cloth and head home.

He would offer some Vadapappu to Seetamma garu, and after a light supper, he would slowly slip into sleep, munching the gram, piece by piece.

One day, as he lay there asleep, Pichayya garu did not wake up. Seetamma garu, who rose from the foot-rest beside him, did not wail at his passing. Shedding a silent tear, she quietly erased her bottu (the vermilion dot worn by married women, customarily removed upon widowhood) and murmured to herself, “All along he was before me; now, he is within me.”

Pichayya garu didn’t achieve anything remarkable. He didn’t resolve disputes, nor did he solve any problems. He simply lived his life, merging seamlessly and timelessly into the flow of time. Isn’t that good enough? It seems, however, that it’s not enough for many people.

Note: This translator has made various attempt to contact the Author and his kin for the permission to translate this story. This story is published for educational purposes only and not for profit.

Satyam Sankaramanchi (1937–1987) was a celebrated storyteller and author from Amaravati, a small village near Guntur City in Andhra Pradesh, India. Renowned for his ability to weave intricate narratives, Sankaramanchi’s stories brought to life the rich cultural tapestry of his native region. His most notable work, Amaravati Kathalu, is considered one of the finest collections of short stories in Telugu literature, praised for its depth and creativity. Sankaramanchi’s storytelling extended beyond the written word; his narrative style captivated audiences and inspired adaptations in various media. His short story “The Flood” gained recognition through its translation into English, while some of his tales were adapted into a television series titled Amravathi Ki Kathayen, directed by acclaimed filmmaker Shyam Benegal. A significant figure in Telugu literature, Satyam Sankaramanchi’s contributions continue to resonate, reflecting the timeless themes of human experience and emotion. He passed away on April 21, 1987, leaving behind a legacy that enriches Indian storytelling traditions.

Read translation of Dr. Veluri Rama Rao on Indian Review.

Leave a Reply