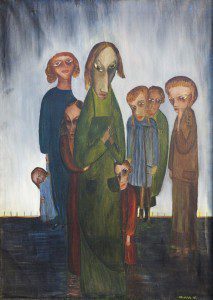

Damião Gomindes, licensed advocate – not one of those who practice in India because they’re not needed in Portuguese Timor, but an intelligent and well-trained legal agent dedicated to his clients – had two defects that took the sheen off his talent. He stuttered, or at least he hesitated often, pretending to stutter before putting his thoughts into words. And he was hunchbacked, his head as if wedged between the shoulders of his frail, rickety body, which gave him the appearance of a beggar.

During his primary school exam, after grilling the boy for an hour the examiner abruptly asked Damião how many subjects a sentence could have. Damião answered that it could have one. In a needling voice the examiner asked him whether it could have two subjects. Damião agreed. Seeing that the boy’s attention was flagging, the damned examiner asked brusquely whether it was possible for a sentence to have five subjects, to which Damião, who was one of the best pupils, piped up:

‘Yes, sir, but it isn’t easy.’

Realising by the titters in the audience that he had been rash in his answer, from then on Damião adopted the system of methodically thinking over his responses before opening his mouth. And so this habit of stuttering before expressing his thoughts had stuck with him throughout his life.

As for his beggarly appearance, it seems he sought to attenuate its effects by growing a beard. The problem was that this hirsuteness merely drew attention to the glint of his tiny eyes and the dark complexion of his face. The most he achieved was to make himself look like an old beggar.

So there the advocate Damião was, hesitating a thousand times, stuttering as he tried to think thrice before expounding to the court the logic of his conclusions, which was both his greatest strength and his greatest weakness. Indeed, striking his chest with the palm of his hand and extending it to the gallery, he looked like a real beggar panhandling passers-by for donations.

His hesitations and his hump grew more pronounced following a series of disappointments Damião suffered at the outset of his career. Even as a lyceum student, when called upon by his Universal History teacher to summarise a lesson, he stuttered so badly that he spent an hour on a single fact that had caught his interest, philosophising and drawing his logical conclusions. Padre Excelso was quite irked – supposing that his pupil had only read the one section and was trying to pull the wool over his eyes with waffle that, truth be told, was expounded quite logically – and awarded him a mark of four. When Damião showed surprise that his logic had only merited such a low grade, the teacher grumbled:

‘You said almost nothing about the lesson.’

Damião hesitated before stammering:

‘But, sir, I summed up the lesson’

‘And I summed up the mark’, the teacher cut in, before leaving.

***

Having completed his schooling and studied Civil Law, there were only two careers open to Damião and his logical mind for which his hump and hesitations would be no obstacle: advocacy or journalism. Since the torrent of charters had dried up he had no option but to enter the world of journalism and so he started out as a typesetter for a political, religious, and current affairs weekly owned by his former teacher.

A few months down the line, the editor having noticed his typesetter’s sensible comments about spelling and logic when they discussed etymology, promoted Damião to proofreader.

It was at about this time that the editor noticed that Damião had a heavy heart. The boy was sad, melancholic, crestfallen. His head appeared even more wedged between his shoulders, his hump more pronounced than ever and his stutter had worsened, though the boy had lost not one whit of his logic. The editor, a perspicacious fellow though hardly a man of the world, realized that his typesetter must have fallen in love. Fearing that Damião’s emotional state might impede his logic, he began to monitor him on the q.t.

Damião the typesetter had, indeed, fallen in love. As he could neither see nor speak to the object of his affections – unable to dance, he didn’t attend soirées and wasn’t a member of the Club – he dragged his Quixotic figure back and forth below the window of his Dulcinea in the dead of night, stroking his newly sprouted goatee.

One night, Damião, who had been reading the ultra-romantic verse of Soares de Passos, despaired of his life. Seeing that the beauty paid his poor figure not one bit of notice, he decided to put a stop to his immense suffering and drown himself in the waters of the creek at Fontaínhas:

‘The Moon glides high’ he cried. ‘What Peace shall be mine on the riverbed, when the gelid waters extinguish the flames of passion that consume this heart “misunderstood by the vagaries of fate”!’ Sitting on that Cais das Colunas, his own equivalent of the Lisbon riverfront, he gazed at the waters that would soon cure his affliction and end his suffering.

The choppy waters began to rise: the tide was coming in. As Damião couldn’t swim and lacked the courage to follow through with his plan, he set his logic to work and reflected philosophically:

‘The waters aren’t still; therefore my body would find no rest on the riverbed. Love is felt by the soul, the soul is immaterial, therefore the waters of the river would be unable to extinguish flames that aren’t real.’

At that moment, a tardy cleaner who happened to pass right before Damião, emptied his bucket in the exact spot the smitten proofreader had chosen to make his final dive. Damião, awoken to the reality of life by the ammonia rising to his nostrils, drove the melancholic ideas of Soares de Passos from his mind. He began to weep, heaving with sobs of rage and shame as he realized his foolishness, the noisome company with which his body, his ardent heart, his logical mind had been about to share their peaceful tomb.

***

Cured of his mad intentions by the ammonia, Damião, who had not yet been cured of his quixotic passion, sat in the newsroom and exercised his logic. He philosophised:

‘In order for her to requite my love, she must know that I love her. In order for her to know that I love her, I must tell her. In order for me to tell her, I must speak to her. In order for me to speak to her, I mustn’t hesitate.’

And, plucking up his courage, he donned his tobacco-coloured cashmere suit, now faded and stained yellow under the arms from years of wear. Putting on his hat and well-worn boots, he set out resolutely for the street where the apple of his eye lived, firm in his decision to declare his love with no hesitations.

It was a hot morning. The sun, approaching its zenith, shot down rays that bounced off the walls of the houses and dazzled the eyes. The young man’s Dulcinea was sitting at the window, as was her wont, gazing at passers-by and pretending to crochet, her cloth purse and a ball of twine in a smart little Huntley and Palmers tin.

Damião walked over from the newsroom with his declaration all prepared. It went like this:

‘Miss, I am but a poor boy who begs a little attention for his pained heart that beats only for you. I… love you, I love you madly, passionately… etc. and so forth.’

Having resolutely reached the window of his Dulcinea, Damião took his hand, which he had been pressing against his chest to control the palpitations of his heart, held it out flat and began to stammer and hesitate:

‘Miss, I am but a p-poor… p-poor… boy…. Who b-begs… b-begs… a l-little… l-little…’

Taking pity on the young man, his Dulcinea plucked her cloth from its tin, untied it and, removing a paisa, placed the coin in Damião’s outstretched hand.

She had mistaken him for a beggar.

The smitten proofreader, realising the error of his Dulcinea, who had given him a paisa instead of her love, fled back to the newsroom in shame. His love, which had resided ever so logically in the hollow of his hunchback’s chest, fled in the opposite direction, swiftly and without the slightest hesitation.

And so, with no hesitation at all, Damião was cured of his first love.

***

Indian Review | Author Biography and Translation Discussion

Indian Review | Translator Biography

Paul Melo e Castro teaches Portuguese at the University of Leeds. He has an anthology of Portuguese-language Goan narratives in English translation entitled Lengthening Shadows coming out through the Goa, 1556 publishing house in late 2014. He is currently preparing a translation of the complete works of José da Silva Coelho, a Goan author from the 1920s, from which the story of ‘The Hesitations of Damião and His First Love’ is taken.

José da Silva Coelho (1889-1944), the most prolific Goan short-story writer in Portuguese, is also, perhaps, the one most completely forgotten by posterity. In the 1920s, however, when he published around 50 of his short satirical narratives in the Goan press, mainly in a column entitled Contos Regionais [Regional Stories], he attained great popularity (and notoriety) with his mordant sketches of the social landscape of Goa at that time.

‘The Hesitations of Damião and His First Love’ (1923) includes a number of topoi and issues that recur throughout Silva Coelho’s work. Three key features worth highlighting here are: a wrongheaded, illusory attempt on the part of the protagonist to overturn a disadvantageous situation; ‘fashion victimhood’, or alignment with attitudes depicted as by that time hopelessly outmoded; and a concluding ambivalent moment of realisation about the true state of affairs. Damião, we learn, has fallen into the habit of wavering when decisiveness is required. The problem is that the humble, hunchbacked Damião is incapable by nature of being any other way, which perhaps reflects certain deep-seated ideas concerning the hierarchisation of society held by the author. There is something within the young Goan’s control however: Damião’s emulation of the Portuguese ultra-romantic poet Soares de Passos (1826-1860), which shows him to be in thrall to a Romanticism that had long fallen from fashion in Europe. The ridiculousness of his failed attempt at suicide debunks the young man’s overwrought navel-gazing, suggesting he should adopt an outlook more attuned to the realities of his surroundings, a proposal that would have had both literary and political implications. Here Silva Coelho echoes certain episodes in Jacob and Dulce (1896), the satirical work by his main precursor GIP (the pen name of Francisco João da Costa (1864-1901), whose biography, concerns and attitudes map quite closely onto Silva Coelho’s. If Damião’s ultra-romanticism is ultimately dispelled by the harsh stench of ammonia, his unrequited love vanishes when the object of his affections – perhaps not inaccurately – takes his outward appearance to represent his inner self. As always with Silva Coelho, who was writing in Portuguese-language newspapers subject to official review, there is no clear-cut message, no epiphany, but we, like his coeval readers, can infer certain undertones for an elite Goan audience waiting impatiently for the Portuguese First Republic (1910-1926) to grant its colonies the autonomy it had promised, even as Indian nationalism, with Gandhi at the head of Congress, gained momentum in the neighbouring territories of British India.

Paul Melo e Castro lectures in Portuguese and Comparative Literature at the University of Glasgow. He has a long-standing interest in the Portuguese-language literature of Goa and is an occasional translator. His translations of Goan literature have appeared in Indian Literature, Muse India and Govapuri, amongst others. His most recent book-length translation is Vimala Devi’s Monsoon, Seagull, 2019. This translation was supported by the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

Leave a Reply