When Aunt Baby told my grandfather she was going to join the S____ Ashram, the old one went mad, as if he’d lost his life’s savings or a hundred mosquitoes had bitten him, all at the same time. I was fifteen, she was thirty. I guess in her mind, thirty was the deadline. Or if you want to look at it differently, perhaps it was the best thing for a woman who initially thought you had to swallow a doll to have a baby. As the years passed, everyone accepted the matter and let her go about her ashramly duties which were mostly charitable and service to all kinds of humanity.

In her forties, her selfless devotion and all her years of strict celibacy were recognized and she was made a chief assistant. The honour was a mixed blessing. She could no longer stay with us. We were used to her being away on weekends and even a week at a time, but now she had to move permanently to the official ashram.

This was a palace a long time ago, donated by a childless Raja to Christian missionaries, who, when they left India, handed it over to the Madras Presidency. For sometime uninhabited, it was used successively for various government purposes. When S_____ Ashram grew famous and powerful enough to have grand political connections, the palace was donated to them, though by then, it had been rather vandalized and was falling apart in many ways.

Already, Aunt Baby shone with importance, her thin face glowed with enthusiasm; the tip of her nose bristled with importance. She smiled with a preoccupied air, like one whose dreams have found strong new material.

I often wondered how come no one had asked to marry her. Once when I talked to my grandmother about it, she said, “There were quite a few proposals, but always something did not match. If the boy was alright, the horoscopes did not match, or if they did, there was the dowry question. Which your aunt was against. One time everything worked – all that was left was the wedding date. Just like that, the boy’s mother died, she was not sick or anything, just unexpectedly, like that. Surely not a good sign, you see. Like that, one after another, and she has a strong mind, you know that.”

And how!

After she left, Aunt Baby kept inviting us to visit her. But my mother put it off on some pretext or other; she really did not want to add my father’s displeasure to her other duties.

So now, the cats settled into a new routine; so did the plants and the dog; so did I. As if Aunt Baby had freed up space for focus on me, my parents renewed their son-in-law hunt; home became a maddening place with hints, pleas, bargains, overtures and all forms of manipulations. What with the events in my life going completely out of control, as you’ll soon see, I did not quite know how to deal with my parents. When they finally said a boy was coming to look at me on the weekend, I went to Aunt Baby.

My aunt was given a room on the east side. She was childishly pleased with her new computer and swivel chair, which she said was stuck and wouldn’t swivel at all. There were faded paintings of lovers on the domed ceiling and the huge, intricately decorated window had a wide seat. I jumped on it and let my feet dangle.

“Took your time to come, didn’t you?” Aunt Baby said, winking at me. She talked about her days at the ashram, and then dropping her voice, she whispered how there was one Sister Armi who was trying to dethrone or de-swivel-chair her. “Otherwise, it is so wonderful. Everywhere there’s sure to be somebody like this. Human nature is human nature.”

“Knowing you, Aunt Baby, I’m surprised there’s only one,” I said and she shrugged with a sheepish grin.

As we admired how she had organized all her things in the room, there was a soft knock on the door and Ranjit entered. I stared. We hadn’t seen each other for almost three days now and for a moment I thought he might be a floating visitation of some kind, like my feet had gone dangling into a dream.

Aunt Baby laughed at my expression. She sat down neatly folding her pallu around her and gestured to Ranjit. “I saw him one day with you when I came to your college and then a few other times. I had to know of course, what was going on – you are my business,” she said to my rounded eyes.

Ranjit came to me, his beautiful eyes, pleading and soft. “She knows,” he said. “Everything. From the beginning. No, no, you don’t have to look at me like that. She made me promise not to say anything to you. She wanted to see how long you would hold out.” As I mulled this over, he gave me a string of jasmine wrapped in lotus leaves. I took it, feeling a huge burden roll away from my heart. How white and radiant were these flowers, without a blemish, each packed bud carrying only fragrance, as if that is the only ingredient that matters. The last few months of my life had been filled with intrigue, guilt, subterfuge, even, I am ashamed to say, barefaced, calculated lies. My father, I lied to, out of sheer fear, but my mother, who is such a tender lady, to tell her whole narratives of lies, and watch her believe everything I said, that had been quite repeatedly unbearable. To have her inquire how “Ranjitha” was doing, to have her say, “Why don’t you bring Ranjitha home sometime?”, the pain was so real I actually developed a cyst beneath my left shoulder blade.

“You could have told me yourself, Nimmy. So secretive, you poor child,” Aunt Baby’s voice censured mildly. “Going on so long, almost a year, like this, what silliness.” She sighed, “I have been waiting for you to tell me. You could have got married before I came here. Now I will have to explain to them, ask special permission and all that. And convincing Sister Armi…,” she rolled her eyes.

“But father.. I am so afraid…What else could I do,” I managed. “You know how he is. I didn’t know what else to do. I had to come today.” I looked at their loving faces and began to feel really tearful as I said, “I have managed to avoid it so long, but now, they’re having someone see me this weekend.”

Aunt Baby sighed two more times. Finally, she said, “We have to have a plot here.”

Ranjit and I said, What, at the same time.

“Yes, a plot is what I’m saying. Your father is…” she squared her shoulders and put out her chest, “Your father. At least if Remy had been a different sort of wife, he might have mended a bit. What’s the use, that’s a completely unhelpful line of thought. Still, we have to think.” She took the jasmine from me, unwrapped it, cut half and wove it into my hair; the rest she put around the little Ganesh on her dressing table. Then she grabbed her handbag and adjusted her hairpins. “Ok, let’s not waste any more time,” she said.

It was four o’clock, when we reached home, Ranjit having dropped us off at the end of the street. My mother, my sister, my grandmother and I sat in the living room. Aunt Baby paced about like a general, her thin shoulders stiff with excitement. My mother’s face went through various shades of incredulity and fear as she listened to Aunt Baby. Every few minutes, she shook her head and clutched her chest, and whispered, No, no, Siva, Siva. My sister giggled half the time. My grandmother watched us all with a sweetly blushing smile. All this until we heard the doorbell ring; then, we scattered like panicked deer; my father stepped in with, “So, how is my holy sibling?”

At dinner, we sat silent, only our eyes moving electrically from one to the other. My father said, “What is the matter with all of you? Your mother has made such a wonderful dinner. But you have nothing to say, I thought you would have some news, Nimmy or Baby?” Then to my sister, “How are your classes going on?”

“I came to talk about Nimmy’s marriage,” I heard my aunt say firmly, as the blood rushed into my ears. There was a quick scramble; it was myself heading for the bathroom, from where I listened, almost fainting.

Aunt Baby’s voice continued in its firmness; she left no detail out. How long – more than a year; the boy – name: Ranjit, occupation: Professor, Madras Christian College; age – 34; religion/caste: don’t know, originally from the North or somewhere. Or actually, a Telugu. My father roared and tried to puncture her firmness; they dug up some other old fights briefly. Then, there was silence.

To my father, I said in my mind, If you will only see Ranjit, you will understand everything. He is like the way trees grow, heavy, solid, the trunk firm and massive. No, not literally, I mean, he is not fat or huge or anything like that. What I mean is, oh what’s the use. Perhaps in some way, he reminds me of you, and that’s what attracted me to him in the first place. Of course, the silence covered everything.

Father did not speak to me for several days, afterwards: I was supposed to be a teacher, not a picker up of men. He threatened to have me locked up if I talked with or contacted Ranjit. I was miserable, my parents were tragic, my sister frustrated, my aunt resolute. When I saw her again, she said, “That was only the opening scene. We have just identified the conflict.”

This went on for almost a week. Then one afternoon, it was a government holiday of some sort, my father was away in Bangalore that day, Aunt Baby came home with a new kind of steeliness on her face. IIT, Delhi had offered Ranjit a position.

“Act two,” she said, briskly to me. “There’s no time to waste, he has to decide soon. Pack some clothes. Have you got a white blouse? Yes, that’s good enough, that’ll do. You are going to spend a few days at the ashram.” At this, my mother fluttered about hysterically, my sister jumped up and down, “Are we going to have an elopement! Oh no, better still, a Gandharva marriage like Shakunthala. Oh perfect, we have the perfect setting in the ashram. Aunt Baby, you’re the bestest.”

Aunt Baby shushed her, “Silly, silly child, what are we going to do with your romantic nonsense. See what your sister has got herself into,” and shepherded me out. On the way, she patted my mother’s shoulder, “Get a hold of yourself, Remy, it’ll all be fine.”

At the ashram, Aunt Baby quickly got me into the guest room, and into the creamy white sari that the other ashramites wore. My white blouse went very well, and I looked a soulful new aspirant. I tried to protest, but there was a silencing, purposeful aura about her, and I actually felt a kind of relief that I no longer had to make any decisions.

It certainly was peaceful in the ashram. Especially, after the last few days. Here, everyone seemed old and they moved about like wraiths whispering mantras, looking at me with pleasant, somewhat loving curiosity. I explored the garden – they grew most of their vegetables – and the cowshed with the two cows and a new calf, Lakshmi; there were five cats and two dogs with three puppies to pet as well. That first day, I helped in the kitchen and then in the laundry room.

It was the evening of the second day. I was cutting carrots in the kitchen when there was a flurry, and Sister Armi came in with great excitement, “Your father is here.”

He was sitting in the visitor’s room in one of the grand left over palace chairs, his knees jerking restlessly. Aunt Baby stood near the enormous window, smiling kindly at him. When he saw me, my father’s eyes widened and his eyebrows drew together; he turned thunderingly to Aunt Baby. “What is this, why is she wearing this sari? What have you done to her?”

I remembered once when I was eight, he had been angry about something and smashed a green vase. I heard Aunt Baby reply in a meek voice, “I just wanted to show her how we lived and what we do and how long it takes to become a full-fledged yogini. I didn’t do anything to her. She was very interested in our way of life. As you can see, it is quiet and peaceful here.” His eyes red and inflamed, he glared at her. They had a harrowingly whispered exchange, at the end of which Aunt Baby marched me to the guest room. “Okay, you can take off that sari now,” she said, her eyes glinting with mischief. “It has served its purpose. He has agreed, somewhat.”

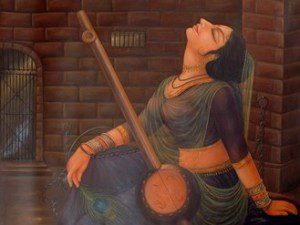

I began to shake, my aunt held me till I stopped, her hands, icy cold. Then she took the fresh string of jasmine from her Ganesh and pinned it on my head. All the way back, the fragrance filled the car and for the first time in many days, my father’s eyes met mine.

Indian Review | Authors | Padma Prasad a poet and painter, was an Assistant Professor of English at Stella Maris College, Madras University. She currently resides in Northern Virginia.

Padma Prasad was an Assistant Professor of English at Stella Maris College, Madras University. Currently she resides in Northern Virginia, and is a federal contractor in electronic records management. Her fiction has appeared in “Eclectica” online (US) and in “Reading Hour”, Bangalore, India. She is also a painter, and her works can be viewed at http://fineartamerica.com/profiles/padma-prasad.html

Leave a Reply