When perfect quiet had reigned for what felt like an hour, I thought it safe to take a quick peek outside. Sticking out my head, I blinked. After hours of sitting cramped in a dark, dingy recess between two buildings, even mild, dusky sunlight pricks the eyes uncomfortably.

The fires had been doused. The smoke was gathering into a thin mist that circled close to the ground – like serpentine fingers reaching out for something invisible. There was no movement on the street, except that of my eyeballs. Like terrified ants, the people seemed to have crawled back to the superficial safety of their holes. Doors and shutters had been torn down and beaten to pulp. Windows gaped. Transmission wires dangled limply from poles, sending out little sparks, as if shooting flares for help. I fancied I could hear half-whispered sighs and groans riding on the stench of putrid ashes and burnt tyres. Perhaps it was only the silence hammering on my ear drums that were still rallying from the din of the last five hours.

“All’s clear,” I whispered.

Eight and Twenty-Three sat up on all fours, ears pricked up and shooting suspicious glances in a manner ludicrously feline.

“It’s fine now.”, I said.

“You sure?”, asked Twenty-Three, peering dubiously over Eight’s shoulder.

“Yes. I’m not sure how long it’ll last, though. We better get going.”

We crawled out of our little hideout and straightened up. Warm blood rushed through our cramped limbs. I looked around at the familiar shops and houses, standing amidst the heaps of stone and brick debris, embellished a little here and there with blood. They seemed scarcely recognizable. Yet this was the same street we had walked through that morning – walked through every morning. The people seemed to have done more damage than the Bulldozer ever intended to do.

Between confused visions of raining stones, piercing shrieks and dancing flames, my memory has retained only a vague idea of what happened that day, or why it happened. But one thing I am sure of – it all began with the Bulldozer. It came that morning to raze a mosque they said had been illegally constructed. I suppose the Muslims expressed their disapproval at this, and the Hindus expressed their disapproval at Muslims’ expression of disapproval. It didn’t make much sense to me then, but I have learnt since that such things rarely do make sense.

What happened after that does not bear remembering.

We walked slowly and cautiously, not wanting to hazard any sound. The silence pressed in from all directions, breathless and listening – straining to catch the soft padding of our bare feet. I was sensible of many unblinking eyes, veiled in shadow, waiting and watching.

It is said that the calm before a storm is dreadful, the calm after is a torment. One troubles with only images and forebodings of disaster, the other reveals concrete and undeniable proof of it.

To us, however, it did not signify. We had nothing to lose or gain, either from the storm or calm.

Such were my thoughts then. But I was soon proved wrong – partly at least.

I felt a sudden tug at my wrist. Twenty-Three was pointing to the ground in mute ecstasy. My eyes lit up – it was shrouded in broken glass. Broken glass! Real, true, broken glass.

We had our collection sacks with us then – the opportunity was too good to be missed. Broken glass fetched a lot more money than paper or plastic. But so far, our luck had given us only an occasional discarded liquor bottle, closeted away in some remote corner of the dump.

“We’re going to be rich!”, said Eight, as we hungrily stuffed our sacks with the little diamonds, heedless of the numerous cuts and bruises our fingers suffered. Not even Ali Baba who had just discovered the Cave of Treasure could have rivalled our joy that day.

I came across a piece, somewhat larger than the rest. It had a bit of wood attached to one end. Possibly it was part of some window pane. Not many hours ago, some pair of eyes might have been looking out through it. It must have been whole and unmolested then, very different from the shapeless, disfigured fragment in my hand.

I held it up and tried to look through it, shutting one eye. The jagged, sharp edges sliced through the scene before me, making invisible gashes. Everything looked strangely distorted and mutilated – very different from what one sees through plane glass. A thousand imperfections and defects that plane glass artfully conceals, were laid naked before me.

“Fourteen! Twenty-Three!”, Eight whispered suddenly, an imperious urgency in his voice. I started violently. The piece of glass clattered onto the street.

Footsteps were approaching at the other end. Harsh, cold, heavy, metallic footsteps.

Only one thought shot through my scattered wits – “Curfews!”. We scurried into a dank, empty shop that smelt of candle wax and took refuge behind a pile of rubble.

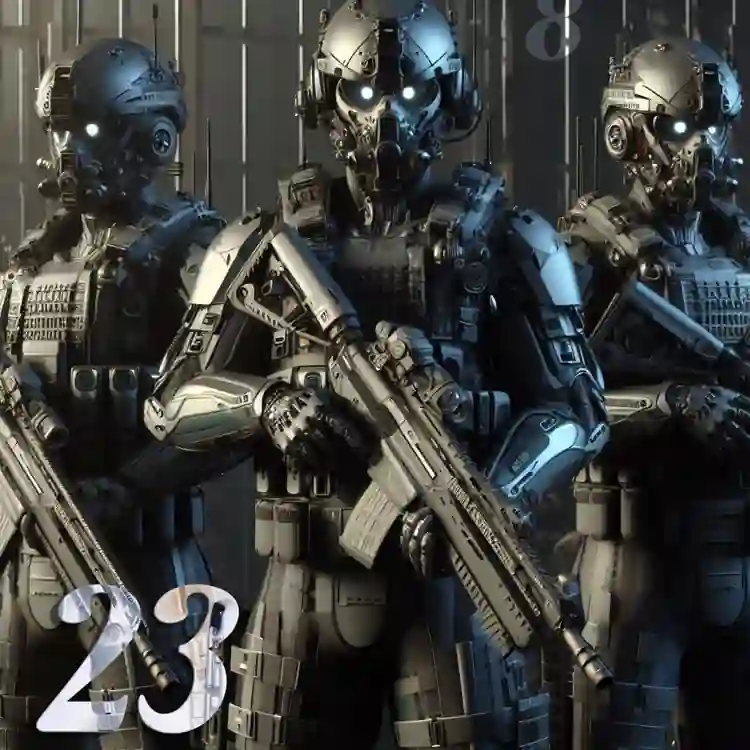

When it comes to the Curfews, reputation always precedes. We had never seen one. But we had heard much about them. Before today, there hadn’t been any rioting in our town, so they were never seen here. Our source of intelligence were from those people who happened to have seen them in neighboring towns. They always came back full of frightening descriptions of these merciless, iron-shod men, who walked around deserted streets after a riot, shooting at sight.

The footsteps grew louder. They were drawing close. I could see them from where I sat, and for once in my life, I realized that gossip hadn’t exaggerated. They were every bit as formidable as rumor had made them out to be – and perhaps even more. There were two of them. Clad in dark green jackets and brandishing large transparent shields, they walked in single file. The one at the head was a trifle taller, with a stiff gait and square shoulders. Another, shorter and rounder, followed. They were in the midst of a conversation and did not trouble to keep their voices low.

“Of course, its’s all their doing – the politicians.”, the Curfew at the rear was saying. “They give us a match to burn ourselves.”

“True.”, said the other one, absent-mindlessly kicking a stone. “But a match makes a fire only on fuel.”

“What do you mean?”

“To burn this we must have oil. Politicians don’t give us that. We lug it around with us everywhere.”

The shorter Curfew snorted his incomprehension, and his companion was obliged to attempt an explanation.

“It is said that Love comes naturally to the human heart. But I think Hatred is just as natural. Love is like the sea, and Hatred the oil trapped beneath its bed. We have both in us.”

“Now, the Politicians – they don’t care for the water. It’s not useful. But the oil – that is precious. It keeps the fires burning. So, they bring it up to the surface, and while we’re running around, igniting fires for immolation, there’s nobody to see how they’re ruling us.”

Just as he finished speaking, they passed by us. For a moment, our eyes met. I shrank back in terror, my chest heaving like a ship on rough seas. He had seen me. Gun shots were expected any moment. Cold sweat lined up on my brow.

Nothing happened. I unshielded my face and looked up. The Curfew had averted his gaze. They had moved on. Perhaps he did not consider it worthwhile to squander his bullets on a decrepit little street urchin.

“Well,” laughed the other Curfew, apparently in an attempt to dispel the tension his friend’s grave talk had created. “at least we have enough sense to keep the ‘oil’, as you call it, where it belongs – buried deep down. We don’t hate each other because of religion.”

“Yes, and even if any fire should ignite between us, we know how to use our seas to snuff it out. I wish most other people were like us. There isn’t a shortage of water, only a lack of willingness to use it.”

They had almost reached the farther end, and their voices considerably faded.

The stout Curfew let out a low, amused whistle. “Honestly, my friend,”, he said, “you are too poetic for this profession. You should be wielding a pen, not a rifle.”

“I would have, if my mother hadn’t gone into hysterics when I suggested it.”

They turned round the corner and their hoarse laughter died into nothingness.

We waited a few minutes in complete silence before daring to breathe again.

“Let’s just go home,” Eight suggested. “We’ll sell our collection tomorrow. Too dangerous to try the market now, with these Curfews walking about.”

‘Home’ was a rickety little shelter we had built for ourselves – bamboo staffs thrust into the ground to make pillars, roof thatched with dry leaves and floor carpeted with gunny bags and polythene. A bit of canvas sheet to keep off the rain completed this specimen of our industry and ingenuity.

Our little palace was situated at the dead end of Street No.2, Champa Colony, on a bit of barren and broken land, where no grass grew and no flowers bloomed. This land, twelve feet long and ten feet wide was a topic of contention between one Aslam Sheikh and one Gajinder Ram who lived on either side. Each claimed with equal vehemence that it had been gifted to his Great-great-grandfather by the then Raja, just after the Revolt of 1857, in appreciation of the services rendered as a spreader of officially sanctioned rumors.

Whether it was the innate kindness of their hearts, or whether the land wasn’t really worth much to them, I don’t know. But neither of them seemed to mind our little encroachment. They never told us to ‘be off’. In fact, they even had the courteousness to pretend that we did not exist, and focused rather on devoting all their energies to continue their land dispute.

My feet moved mechanically. I was lost in thought, brooding by turns on oil, water, matches and pens, when a seemingly out-of-the-context question by Twenty-Three roused me.

“Which was which, do you think, Fourteen?”, he whispered.

“Which was which what?” I asked, not understanding.

“The Curfews.” he said. “They said something about not hating each other because of their religions.”

“Ye—es.” I hadn’t paid much attention to that part of the conversation.

“So, which one was the Hindu and which was the Muslim?”

I puzzled over this question without arriving at a satisfactory answer. I was saved the embarrassment of professing my ignorance by Eight’s intervention.

“Skull cap, beard, tilak, saffron – they weren’t wearing any of those. It’s not easy to tell them apart without such things. They look similar otherwise. In this case, it’s even harder. The Curfews wore the same clothes.”

“Maybe”, I said, “– maybe, if we knew their names, we could make out. Hindus’ and Muslims’ names sound different.”

“Say what!” said Eight, smacking his forehead and forgetting to keep his voice low in excitement. “I’ve just figured it all out.”

We looked at him inquiringly. I was the one who usually did the figuring-out.

“It must be that people’s names decide what religion they’ll belong to. They can don their skull caps, wipe off their tilaks – get rid of every mark of distinction, and try to look and speak the same, but they can’t do anything about their names. They’ll always have those to give them away.

“And what’s more, I think we don’t have a religion because we don’t have names!”

He looked both surprised and satisfied with himself at this unexpected burst of wisdom. I forbore to prick his pride balloon. There seemed to be some sense in what he said (a novelty for Eight).

I had always wondered where people got their religions from, and why we hadn’t one. This new name-theory seemed to offer some explanation.

There’s a sad little history concerning our names. If anyone wants to whip out their handkerchiefs, now’s the time.

We didn’t have names. Our parents had apparently forgotten to name us before they cast us away. Then the Abode for the Abandoned took us in. They found out the we didn’t have names, and didn’t trouble to give us any. They did give us allotment numbers, though – Fourteen, Eight and Twenty-Three. And when they sent us off, as part of their post-Covid economization drive, we simply stuck to those numbers. They served the purpose just as well. After all, calling each other numbers isn’t very different from calling each other names.

A slight digression. In defense of the Abode for the Abandoned (lest they be considered heartless and mercenary), I would to say this: true, they turned us out, but they made sure to equip us with all the possible means (three gunny bags) of self-reliance and distinguishing ourselves in our careers as rag-pickers.

Back to names. So, you see, what began as a flagrant display of inept parenting, has left us for life without a name – or a religion (if Eight’s name-theory is assumed to be correct).

We turned the corner of Street No.2. Long inured to the sights of damage, the dilapidated condition of our own street did not strike us as anything remarkable.

“For once,”, said Twenty-Three, “I’m thankful that we don’t have names. Thankful, because being nameless also makes us religion-less.

“Before today, I always used to regret it – not having a religion, you know – not belonging anywhere. But now I’m happy. If this (pointing all around) is what comes out of having a religion, then no, thank you – I’m better off without one. So long as we’re not one of them, we’re safe from all their rioting and fi—”

The words were pushed back down his throat, choking him. We stopped in our tracks, frozen to the marrow. A queasy feeling gripped our innards. The last rays of the dying sun watched the horror stamped across our faces.

We were at the dead end. Aslam Sheikh’s wooden door had been wrenched from its hinges. It lay battered on the ground. Scorch marks scarred the walls of Gajinder Ram’s house. But our eyes had not the leisure to bestow upon these sights.

The taunting wind breathed in my ears a reminder of my own naïve thoughts – “… Nothing to lose …”. The sun was extinguished. A suffocating darkness closed in. We still stood there, searching with helpless eyes the dismal, charred wreck for a fleeting glimpse of our home.

Somewhere above, a sudden glimmer caught my eye. I looked up, blinded a little by silent tears, at the old, sagging tree. A piece of glass was caught in its branches. The moonlight danced on it in lurid ghastliness, laughing in my face.

I had seen the world through broken glass – and it was a hideous, ugly world.

***

Sahar Imteyaz is a high school student from Bangalore with quite a reputation for not being taken seriously. And that’s expected — she has neither any qualifications in creative writing nor any accolades to recommend her — none of those things that really matter. She’s just an obstinate little voice that wants to be heard.

Leave a Reply