I’m an extremely sadhu type of fellow. All my life, I have avoided confrontations, preferring to compromise and, if necessary, surrender. I’m really fine with this, though, sometimes I wonder: is it because I am a coward or a pacifist?

Haven’t yet found an answer to that, maybe never will. That’s fine too. When my mother is extremely stressed, she says I am a complete mistake — I should have been born a girl. Since I published my first novel and then followed up with two others, and have become a successful writer, her stress is replaced by tolerance and good humor.

So, here I am in Pandu’s house in Lingapeta, the village where I was born. This is the house, where my father was once the dhobi, where, as a child, I could only enter through the garden door at the back. But today, I am welcomed like a prodigal son; I enter through the giant front doors. When Pandu actually gave me a coir-strung cot on the side verandah to sleep on and even apologized that he couldn’t give me a room because there were just too many relatives, I was very moved; never was I more thankful to be a celebrity.

I had arrived just before noon and have been waiting ever since to catch a glimpse of my Manju. Manju is Pandu’s sister and the heroine of all my novels; actually, all my women characters are versions of Manju. She is all I have taken away from Lingapeta, kept alive constantly in my mind and on every page I write. My only worry is that sooner or later, some reviewer is bound to comment on the similarity of my women characters.

I was born with love for Manju. I do not ever remember a time when I did not love her. Something like breathing. We have eaten, bathed, slept, studied, peed in the pond, been sick together; she is an extension of myself. But as I grew up, I could see no future in it. It’s the old story, me, a dhobi’s son, she, an upper caste girl; the more I thought about it, I saw only darkness and pain ahead.

As soon as I completed high school, I left Lingapeta, thinking I will never return; until I met Pandu in the sari shop in Chennai and he said, Manju is getting married. Somehow, that news unleashed reams of memories and before I knew it, I was planning my return. I said to myself, that’s what lovers are for — they participate in every important event in the beloved’s life.

It is February, but the heat is quite unbearable. Lingapeta is very close to the river and it can become breathlessly humid. After a wonderful lunch, I dozed off and woke up to hear, “She’s lucky to have this chance even. When I first saw her, I thought, what can anyone do with such a skinny one, such a flat chest.”

There was a chuckle and another elderly voice replied, “Still, to tie her up with a much older man like that, I feel sorry for her. It’s not as if she has no money or land. It will be so difficult for her; ten or twelve years older, we can understand, but thirty…?”

I let this information sink into my head with a vague sense of discomfort. The last time I saw Manju, she was about fourteen. Yes, she was a rather slim, sprightly girl; I tried to remember what her chest looked like and realized I had no clue. This is how they spoil everything, I fumed at the old women, so crassly dismissing my Manju purely in terms of her physical dimensions. To shake away my disgust and sweat, I stripped at the bath area near the kitchen and had a cool wash. Just as I was toweling myself dry, Pandu joined me. He too was sweating profusely. He pealed off his soaking white shirt, unwrapped his dhoti and adjusted his loin cloth. “Too many last minute problems,” he said. “We have no flowers yet. The flower truck was supposed to come two hours ago, if it doesn’t get here soon, there will be no time even for decoration.”

“Where is Manju, I haven’t seen her anywhere?”

“She must be inside somewhere, with all the women.” Pandu lowered his voice. “I am not too happy about all this, Gopi. She’s so young. There was no need to settle her so soon. You know how she likes school, she is studying very well, too. Times have changed, but Thaathagaru does not realize it. As if we wouldn’t get a good boy after a couple of years.”

“What does Manju feel?”

“What can I say! She is as playful as she was when you left, it’s all a fun for her, remember her dolls’ weddings? Now she is the doll, that’s all the difference.”

Pandu combed his wet hair with his fingers.

I said, “So what’s he like, your new brother-in-law?”

Pandu shrugged and assumed a rather odd expression. “You have to meet him. Come, let’s go and see him, now.”

My discomfort increased into a mild distressing sensation. We made our way across the courtyard, to one of the rooms on the side of the house allocated for the bridegroom’s party. The door was ajar; before Pandu could push it open, a group of women came there and one of them said, “There you are, Pandu, we have been looking all over for you.” As they pulled him away, Pandu gestured to me, “Go on, you go in and meet him.”

I stepped hesitantly through the doorway. Inside, a man, who must be at least in his fifties, stood, smoothing his enormous moustache. I could not make any sense of it. I looked around to see if there was anybody else, but no. My heart burst into flames; so, this was why Pandu was not happy about this match; I could see now what the old ladies had meant earlier that afternoon. I could not believe they would cast my precious Manju into the hands of this ancient buccaneer. He glinted as he moved, with a gold shirt, a machine cut gold chain on his chest and a matching hefty bracelet on his wrist. His features were so crude and rustic, his nose so bulbous, I could not say a word; nor could I hear a word he was saying. I have never felt so shaken in my entire life, my hands trembled and a shudder clung to my spine. What had they seen in him, that they sort to burden Manju with such a life. He moved towards me, his hand outstretched, talking, again I was deaf; he smiled and his left canine tooth was made of gold. I shrank back in uncontrollable revulsion. I stepped out, breathing heavily, gasping for air. Some children who were playing outside looked at me strangely. There was no way this was going to happen. Now I saw the whole purpose of my existence; my responsibility was clear. I would prevent this event at all costs, even if it meant death or anything.

I managed to finally find Manju in one of the rooms way back inside the house. I guess she was happy to see me. Her whole face lit up for a brief second and then her expression went neutral. I had no time to interpret this. I pulled her into an adjoining room and shut the door. She had changed in a strange way. There was a calm aura about her, her complexion suffused and glowing as if lit from within; she looked very mature; I was startled at how classically perfect her features were – the curved eyebrows, the full lips, the straight nose, all set in a sharply defined facial structure; her eyes were lined dramatically with black. She is still extremely slim, like a gazelle, the same elegant yet awkward gait.

“Manju, I just met him, your bridegroom. You cannot do this, Manju. I cannot let you do this.”

She considered my words with her head tilted to the left, the way she is when she tries to make sense of a math problem or a difficult word. Finally, she said, “When did you come?”

“When did I come? I came in the morning, just before noon. Never mind when I came. I never thought I would return to Lingapeta again. I met Pandu in the sari shop. That’s when I knew you were getting married. There is a meaning in all this. I did not think to see this happen. I just saw him in all his wedding finery. Manju, Manju you will be completely wasting away your life.”

“I have to go back now, Gopi, they will be wondering where I’ve disappeared.”

“Does nothing I say make any sense to you?”

She looked a little vexed now. “What do you expect me to do. My three cousins, younger than me, all married. My parents won’t let me go to Hyderabad or Chennai to study further, no, that’s out of the question. Thaathagaru knows these people very well, they are very wealthy. I have no real argument for saying no.”

That made me pause a bit. Thaathagaru, Manju’s venerable grandfather was a man I admired enormously. Highly learned, he was very modern in his thinking; I owe so much of my understanding of life to conversations with him. That such a man would choose this direction for Manju, it left a bitter taste in my heart; he was obviously just a talker, when it came to reality, he was just like everyone else. I could not condone it. Even I was more suitable than a fifty year old man.

I continued, “And that’s a good reason, to go along with this dreadful scheme? It’s not anyone else’s life, it’s your own life, Manju. You can’t, I won’t let you throw it away like this.”

I looked around the room desperately. Books lined two of the walls and against the third there was a desk with a typewriter on it; beside it, a book of love poems someone had been reading and left open. I snatched it and waved it at her. “A life without love, without passion, that’s a terrible punishment for you. Come away with me, I will take you with me and you can stay with me in Chennai till you decide what to do. Or, if you prefer, I will move to a friend’s house, or you can stay with my mother, if you don’t mind, it will be for only a few months, till you decide what to do.”

Manju’s eyes widened and flashed angrily. “ Ah Gopi, you think I am one of the heroines in a novel, who will do mad, stupid things and everyone will admire them. Reality is completely different from what you imagine it to be, Gopi. Now, enough, stop this silliness, I have to go back.”

For answer, I opened the book to Emerson’s “Give all to Love”. I read out:

“Give all to Love

Obey thy heart;

Friends, kindred, days,

Estate, good-frame,

Plans, credit and the Muse,—

Nothing refuse.

’T is a brave master;

Let it have scope:

Follow it utterly,

Hope beyond hope:

High and more high

It dives into noon,

With wing unspent,

Untold intent:

But it is a god,

Knows its own path

And the outlets of the sky.”

I translated the words into Telugu and the meaning sounded even more beautiful. “Love is the only reality, Manju. Does he, can he make you feel like this?”

I started to read again, but she snatched the book from me, snapped it shut, and inserted it among the other books on the shelf nearest to her. She went to the door. “Stop, stop it, Gopi, stop your fine drama here. It’s a little too late for such questions now, Gopi,” she said.

I played my last card. “Why should you listen to anything I say, Manju? I am after all, a dhobi’s son.”

She lowered her head almost as if to ram into me; her nostrils flared and her shoulders went back. I involuntarily stepped backwards.

“You’re a nice one to talk. Yes, that’s true, dhobi’s son, how can we all forget that? There’s no escaping that, is there?” We stared at each other, our wills battling for control. In our staring contests as kids, Manju always won. Now, she was the one who looked down and said softly, “Things change you know, Gopi. That excuse has no value any more, Gopi, you already used it when you left me before.” Then she drew herself up proudly, “It’s no concern of yours, dhobi’s son, is it, what I do with my life?”

She was gone, before I could react.

I could not sleep that night. My feverish brain plotted one scheme after another. Through it all, her last words kept repeating in my head like a fiendish chant. When dawn broke, I sat up with a firm resolve: it all boiled down to: somehow, this bridegroom fellow should not be found when the priest chants his mantras and they are about to perform the marriage ceremony. But the how of it was a little sticky, literally.

Through the day, I was restless and so distracted that I was of no use to anyone. Pandu’s mother said the heat might be affecting me and to take rest till the evening.

Near the verandah, Somaiyya, the odd-job man, was de-husking a whole mountain of coconuts. For this, he was using a very vicious looking curved blade which glinted as he swung forcefully into the back of the coconut. He had two such instruments; for variety, I suppose. I could easily take one of them, hop into the room where the golden bridegroom was steeped in some fantasy, and just plunge the tip into his neck. The knife was doing such short work of the hard coconut husk, how easy would it be on the human neck. That would do it, once and for all. Except, I am really not made for these kinds of projects. Sure, I can write about it in my novels. Manju, in one of her incarnations as warrior heroine, is always plunging metal into all sorts of bad people.

He was not really that bad, after all, not bad enough to be killed. No, I take that back. If you are fifty and going to marry a seventeen year old, it’s most confirmedly bad, enough to warrant the death sentence, enough to make me lose my reason, enough to damage everything I hold sacred. The other less frightening option was to lock him up. I remembered they used to have a godown a few yards behind the house, where they stored excess grain and sometimes, sick cows used to be kept there. I went out and checked; it was still there; I checked whether the door was strong and would hold.

I walked around the house several times, unable to get the courage to lure him into my trap. It would soon be six pm. If I did not do it now, I might never be able to live with myself. I hovered before his room two or three times. My eyes felt blurry and I paid no attention to anything that went on around me.

In the end, it turned out to be surprisingly easy to get him there. I even felt somewhat sorry for him. All I had to say was, “Pandu has planned a little something for you behind the house, before the final ceremony. He sent me to ask you to come.” He laughed knowingly and seemed to have forgotten my strange behavior of yesterday; he was so happy. Why wouldn’t he be? If my plan doesn’t work, he would be married to Manju by tonight.

It was a proud moment when I pushed the padlock securely. To make doubly sure, I had brought my own lock; there was always the chance that someone might pass that way and hearing his pitiable cries, might release him prematurely.

I returned with a sense of fulfillment. It was almost half past six. The auspicious time was 8.03 pm. Only a little while to go. The enormity of what I had just done crushed me. I could hardly stop myself from rushing back to the godown and releasing the bridegroom. What would happen to Manju’s future? There are any number of stories of women being left alone in the wedding pandal, their grooms refusing to marry them either because of dowry or some other issues. The woman’s life would be ruined forever; they frequently committed suicide. I saw the headlines: Jilted Young Bride Hospitalized after Suicide Attempt; or Celebrated Young Novelist Locks up Bridegroom of his Childhood Sweetheart.

And to confront Manju’s grandfather, I don’t think I have the guts for that, I might as well be dead. Yet, I am not going to be remorseful now, nothing could be worse for a young girl than a future with an old man. Anyone would see the injustice of it; there needs to be some legislation about this, a legal age difference. I may take it up as my cause in the future.

At about 7.30, I heard the drums start a different beat. A new sound, a trumpet was added to the din. I would have liked to leave the village quietly, before the inevitable discovery, the tears, the devastation. Still, my sense of responsibility and a horrible fascination for the actual end drew me to the pandal. Let me be honest here: there was the tiny hope that I could carry Manju away to Chennai; that I would be her valiant rescuer.

Pandu met me en route. He looked really stressed, his red face reddened even more and gleaming with sweat. “I’ll be glad when all this is over. What with missing aunts and uncles, it’s a wonder the bridegroom too hasn’t gone off somewhere.”

My heart fluttered sickeningly. I studied his face, did he know?

“What do you mean, Pandu?” I croaked.

“The aunt took off to the next village to see a tent show. She’s not back yet. And the uncle, no one knows where he went.”

We were interrupted because Manju’s grandfather made his entrance. He is an imposing man, tall and aristocratic; he is dressed in a crisp silk kurta and dhoti. He is supported by two young men, his hands around their shoulders. He acknowledges me with a majestic nod. They guide him as close to the little raised dais as possible and settle him into a red throne like chair.

Manju is sitting in front of the priest and they have a little fire going on. I would have liked her face to look a little tragic; instead, I have to admit she was quite radiant. The crimson wedding sari she wore suited her colour very well. The flowers had obviously arrived, there were strings of roses and jasmine everywhere. I hoped intensely, she would see me and give me one last meaningful glance; but she was focused on what the priest was telling her to do. He finally intoned the last mantras, looked at his watch and said, “It’s time, where’s the bridegroom, please bring him.”

All our faces turned towards the side of the pandal, where the bridegroom must enter. The crowd sighed and craned as one unit: a young boy, scarcely older than Manju, emerged, carrying a garland. I watched disbelievingly. He made his way towards Manju and seated himself beside her. Everyone leaned back and resumed their noise. The drums went mad and then this ‘bridegroom’ garlanded Manju and they tied the three knots around her neck. What have I done, my stomach contracted with misery. Beside me, Pandu whispered, “See what I’m saying, he is too young for her. Actually, I think he is a year younger. As if she couldn’t do better. Sometimes, Thaathagaru thinks he knows everything and makes arrogant mistakes. Any need for this?”

In the shower of rice that followed, I sat down on a chair, as my knees gave way.

The man I had so confidently locked away was none other than the bridegroom’s maternal uncle. I apologized in every way imaginable; the only reasonable explanation being that, as a writer, I was filled with peculiar imaginations. Fortunately, when weddings end successfully, most of the odd things that happen are forgotten or laughed off. But I know I won’t be on the uncle’s favourite list for a long time, if ever.

The next day, Manju left for her new home with her new husband. The house was soon deserted as one bunch of relatives after another left. I felt completely exhausted and was lying on my cot, when Manju’s elder sister came to sit with me.

“Haven’t had a chance to talk to you since you came, Gopi. We saw your name in the papers, we were all so excited. So, when are you getting married? Are they looking for you?”

“No time now, really, Akka. The writing keeps me too busy.”

She wiped her face with the end of her sari and smiled. “How much you cared for Manju. She too. Pandu and I, we always thought she would run away with you. And then we would have one of those scandalous secrets in our house, too.”

I shook my head and said, “Not a chance. I am too much in love with my heroine and might just marry her.”

She laughed and went away. A chicken had escaped from the garden and was walking about in front of the verandah steps. I watched it scratching the soil and jerking its head restlessly.

In the evening, Pandu drove me to our little station; my train was about fifteen minutes late. I embraced him and said, no more excuses, he must visit me, we should never lose touch again. As soon as I got into the train, I spread out my bedding and lay down; a great depression was moving in on me: my love has been so worthless. What if I am a dhobi’s son. That has not stopped me from breathing, living, writing. I was the one who should be punished for letting myself get in my way. Then the image of Manju’s Thaathagaru flashed before me. His baleful stare, my father’s possible shame, the humiliation, the betrayal – I shook my head. No, not for me. No, as I said at the beginning, I am a sadhu. The nature of my love is to create and never tire of creating Manju again and again.

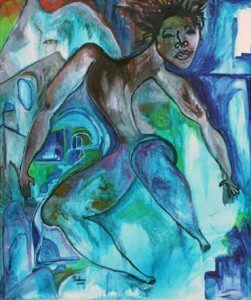

Indian Review | Authors | Padma Prasad a poet and painter, was an Assistant Professor of English at Stella Maris College, Madras University. She currently resides in Northern Virginia.

Padma Prasad was an Assistant Professor of English at Stella Maris College, Madras University. Currently she resides in Northern Virginia, and is a federal contractor in electronic records management. Her fiction has appeared in “Eclectica” online (US) and in “Reading Hour”, Bangalore, India. She is also a painter, and her works can be viewed at http://fineartamerica.com/profiles/padma-prasad.html

Leave a Reply