-

A Day Passed Off | Satyam Sankaramanchi

This story is part of Amaravati Kathalu, an anthology of Telugu stories set in the rural milieu of Amaravati, a village on the banks of the Krishna River in Guntur District, Andhra…

—- “Anyone who ever gave you confidence, you owe them a lot.” — Truman Capote

670 authors | 269 Short Stories | 588 Poems on IndianReview to read.

Literature without Borders…

Connecting Cultures through Literature from around the world…

Fiction

-

The Theft | Amita Samant

Dense clouds gathered steadily, forming a thick grey ceiling under the sky. The bellowing winds warned the coast about the powerful cyclone forging ahead in its direction. Rows of tall coconut trees swayed violently as the wind hurled its wrath over them. It was a little past noon, but the sun had sheltered itself long…

by: Amita Samant

-

Back Home | Juno Negi

I “Light nahi hai!” Sandeep greeted me as I thumped the uneven sack on the floor, where it fell with a dull thud. “Wah! Look at the vegetables you brought back this time!” he exclaimed, grinning at the sack before I could complain about the heat.As I struggled to let go off the bag from…

by: Juno Negi

-

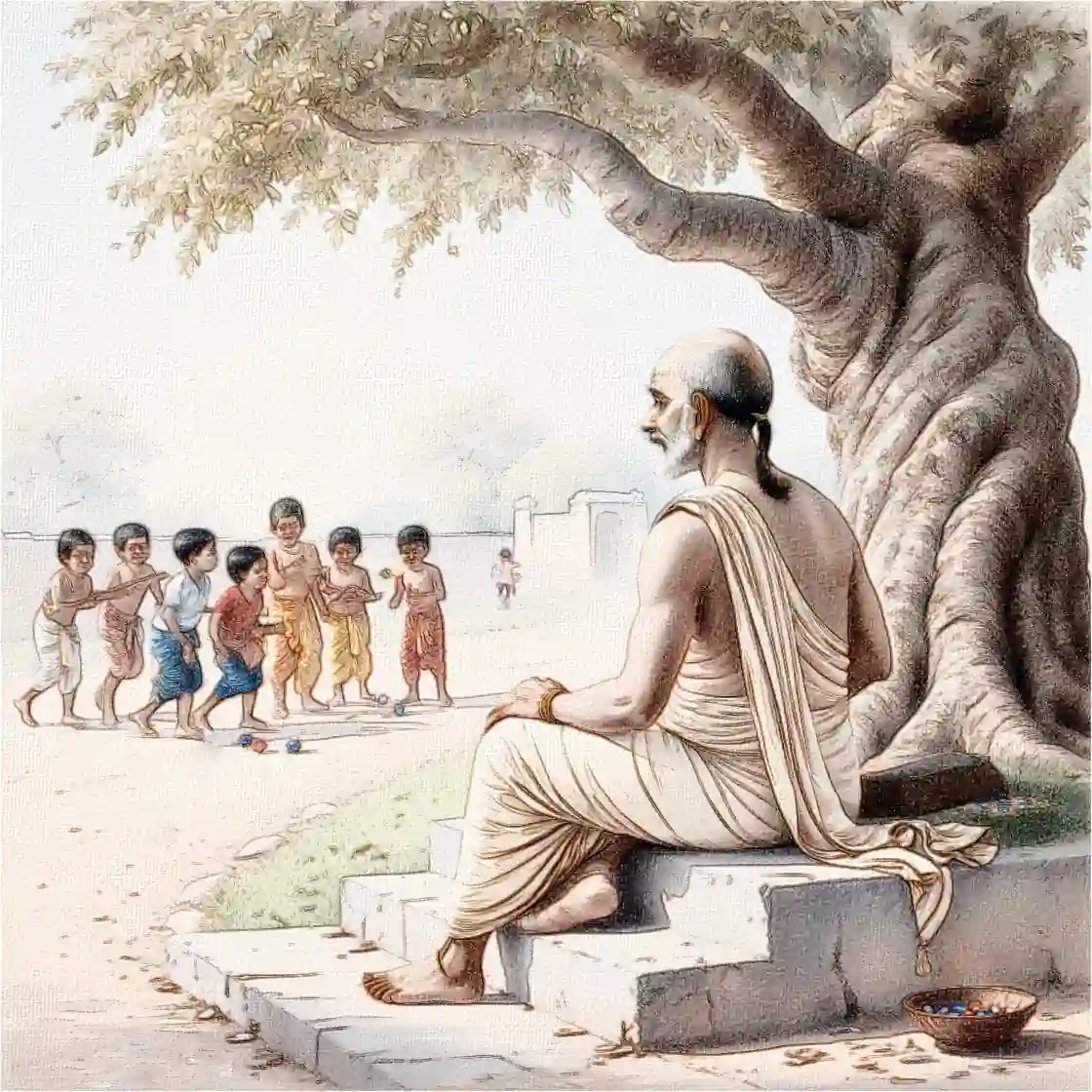

Pilgrimage | Konyala Sai Ram

The man, short, never allowed by the burden of responsibilities and financial needs to grow tall; dark, naturally, due to working in the broad daylight and melting heat. A usual day in his life would start as early as 6 in the morning and last till 6 in the evening allowing ample time in the…

by: Konyala Sai Ram

-

Returning to Jingzhou | Changming Yuan

This piece ‘Returning to Jingzhou,’ is an excerpt from Changming Yuan’s novel The Tuner After spending more than a week with her parents in Songzi, Hua was supposed to join you today for a nine-day secret honeymoon tour to Shennongjiao, Zhangjiajie and the Phoenix City. But circumstances forced her to return to Zhuhai to accommodate her sister-in-law’s…

by: Changming Yuan

-

The Ouroboros and the Djinn | Salmah Ahmed

Farah yawned and cast a perfunctory gaze at the road. The headlights of their speeding Land Cruiser, illuminated the road ahead. Yellow street lights lit up small patches of an endless stretch of gravel like shallow pools of liquid amber. They were headed to Atharan Hazari, a small town in the Jhang District of Punjab in…

by: Salmah Ahmed

-

Destiny Averted | Salmah Ahmed

That Tuesday, the 17th of July 2007, was the kind of day that settles on your head like a cauldron of boiling water, before sliding down your nape and spine, not with fiery heat, but with the slow, insidious creep of melting wax. It gathered like clay, dust and sweat copulating, in the folds of…

by: Salmah Ahmed

In the Spotlight!

Poetry

-

A Boat Returning Home | Udita Banerjee

I walk on the brown tiles of my terrace. The mind dwindles between the mundaneness of life and the deliciousness of the moon in its…

-

Old Men | Brandon Shane

The old men hang on their porchesas dying crows stare at the worldon rooftops, electrical wire, askingwhy they’ve been allowed to livewhile others have been…

-

Snakes | Kamayani Vashisht

I often wonder what came of the neighbourhood boysWho threw a dead snake at meWhile playing in the apple orchardForty moons agoDid the highways they…

-

Simplicity: A Simple Game | Sushant Thapa

I need to rest,I need to begin again.The days are like long promises,The thirst-quenching desireIs the evening breezeTouching my body.Too ridiculous to talk aboutBodies making…

-

Author | Nandita Dutta

I am your author, you’re the unfolding story,on the pages of these racing years.It began with books I read to prepare for youabout how you’ll…

-

Saviour | Nandita Dutta

You know the darkthat can drown words?I come from that world.the dark is too dense for me to reach out,to pick words that mean thingsit is…

-

Brochure | Ian C Smith

(from Middle French: to prick) Former Post Office it shouts, High Ceilings./ Lots of Shedding wryly conjures a verb,/ heart pricked, irony defending feelings,/ warped…

-

Akhtari Dreams of the Spectral Light of Eternity | Steffen Horstmann

As she sings the taffeta clouds brighten with stardust, luminescent forever–With the lights of Lucknow pulsing in the sky’s mirror, opalescent forever. She can see through…

-

Ellora | Steffen Horstmann

Kabir saw ashes pulse with light and whirl like snow in the caves,Through smoke where Shiva’s aura gleamed like a rainbow in the caves.Mirabai wrote…

Click and check our collection: